100 Years of Poetry: “In the Middle of Major Men”

During the winter and spring of 1910–11, Harriet Monroe worked her way through Chicago’s downtown Loop, talking with lawyers, bankers, meatpackers, and real estate tycoons about poetry. Monroe was just over 50 years old, no longer the young poet known for the Columbian Ode that she had written for the opening ceremonies of Chicago’s 1893 World’s Fair—an ode performed for nearly 100,000 people. Monroe was trying to raise money to launch a monthly magazine dedicated to the new vers libre, not the classical, academic poetry that she had once written. Her ideas about poetry had changed over the years, though her desire for a large public audience for it had not.

On these trips to raise money, Monroe sailed past secretaries. “In visiting men’s offices I developed certain rules,” she would later explain. “I never resented refusals from people I could not persuade…. But I would not be stopped by secretaries, those polite evaders whom big men placed at their doors to turn away importunate solicitors like me.” Both confident that her plan deserved consideration and also willing to belittle herself before “big men” (a classic move), she navigated the egos and ambitions of Chicago’s culture-conscious business class in order to win support for her magazine.

Monroe is the most celebrated woman of Poetry magazine—and arguably its most important editor—though many women helped to edit Poetry both in Monroe’s time and throughout the magazine’s 100-year history. They include Monroe’s indispensible first assistant, Alice Corbin Henderson; writer and war correspondent Eunice Tietjens; poets Jessica Nelson North and Marion Strobel; and Margaret Danner, a highly successful African American poet who worked with Karl Shapiro and Henry Rago in the 1950s and 1960s. Like Monroe, these women navigated a larger literary culture dominated by men.

I.

In the middle of “major men,” to use Wallace Stevens’s phrase, Harriet Monroe is a figure who worked behind the scenes, as did many of the women who followed her at Poetry. Monroe contrasts sharply with Poetry’s foreign correspondent, Ezra Pound, who ambitiously sought to inhabit the center of an avant-garde literary scene. (“I do see nearly everyone that matters,” he wrote in his first letter to Monroe in 1912.) However, in terms of discovering new poets, cultivating their work, and choosing when and how their poems would appear, Monroe was Pound’s equal. She realized that “who matters” meant more than Yeats, Eliot, and Pound; it included poets from the Midwest and West, African American writers, and minor poets who wrote a few important poems. It also included Wallace Stevens—whose work Monroe published when he was still unknown—a poet whom Pound never once acknowledged in his letters to Monroe. In the profuse correspondence between Monroe and Pound, Pound’s voice is voluble and dominant: he often takes credit for Monroe’s significant achievements as editor, and he violently disagrees with her about how to cultivate an audience for poetry.

To temper Pound’s voice and tell the story of Poetry magazine through archival records is to see that the magazine was extraordinarily indebted to the labor of its women. Indeed, in the beginning the staff was mostly women. Staffer Jessica Nelson North wrote to Monroe in 1919, “I hear you have imported a man! Mr. Fuller tells me it is quite without precedent.” In “Men or Women?” (June 1920) Monroe quoted the Philadelphia Record, which found that “[t]he vigorous male note [is] now seldom heard in the land, and almost never at all in the pages of POETRY.” This editorial writer had concluded that Monroe and her staff were women “with radical and perverse notions.” But when Monroe looked up the numbers, she was surprised to learn that from April 1919 through March 1920 she had printed 64 men and 41 women; in total pages, the ratio of work by men to that by women was “almost exactly two to one.” Men still dominated the pages of Poetry despite the fact that the editorial vision of the magazine, especially in the beginning, came from women. Soon after this point, however, the ratio would equalize and then tip in the other direction: more women than men were published in Poetry’s pages in the early 1920s.

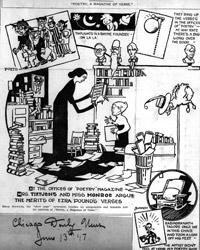

A photograph—taken in Poetry magazine’s office at 543 Cass Street sometime between 1912 and 1922—shows Monroe at a desk stacked with manuscripts and letters. According to Monroe, the office had a shabby, domestic elegance and was fitted with a wicker rocker known as the “poets’ chair,” where many of the poets who visited Monroe would sit. The chair was “an ancient affair,” as Eunice Tietjens described it: “most of the poets of our generation have sat in it and the thing really belongs in a museum.” Monroe might brew for her poets a pot of coffee over an open fire in the vacant lot next door.

That Poetry’s early office was housed in an old family home underscores the fact that the magazine was conceived by a woman and sustained by her mostly female staff. “I had never been the actual mistress of any home which had sheltered me,” Monroe would later write, “but this little kingdom was mine, and I rather enjoyed dispensing its fleeting hospitalities.”

Monroe may have been a nice hostess, but she rarely lavished praise on poets. Her selection of poems was uncompromising. She would defy those businessmen-skeptics who, when she knocked on their office doors in 1910, could not be persuaded that the magazine would be anything but a home, in Monroe’s words, for “petty rhymesters under soft feminine editorship.”

II.

There was no person Monroe valued more at Poetry than Alice Corbin Henderson. Monroe sought out Henderson’s help as a reader before the first issue went to press in October 1912. Henderson was responsible for discovering the work of Sherwood Anderson, Edgar Lee Masters, and Carl Sandburg—most notably Sandburg’s poem “Chicago” when he was an obscure newspaper reporter. Henderson herself was a poet whose work was shaped by her experiences in New Mexico, where she moved with her husband, the painter and architect William Penhallow Henderson, to treat her tuberculosis in 1916. She published several well-received volumes of poetry under the name Alice Corbin, and she edited an important collection of Southwest poetry, The Turquoise Trail (1928). In New Mexico Henderson befriended Willa Cather and worked for D.H. Lawrence as a part-time assistant and typist; the work of both writers appeared in Poetry magazine largely because of Henderson’s influence. From Santa Fe, Henderson continued to work actively as associate editor for six more years and wrote sharp, often witty reviews and essays for the magazine through 1922.

Monroe and Henderson refused to turn Poetry into a mouthpiece for influential East Coast writers or for the artistic trends current in European cities. In the photograph of Monroe in her Cass Street office, the Native American pot atop her desk attests to Henderson’s influence and Monroe’s lifelong fascination with the American West. A few early issues of Poetry focused on Native American and New Mexican cultures. In November 1917, Henderson’s “New Mexico Songs” opens with a poem announcing a defiant turn away from the city and its “fierce modern music.” The lines seem a direct reply to Sandburg’s vision of the “stormy, husky, brawling” city of Chicago. In the special August 1920 “New Mexico Folk-poems” issue, Henderson’s essay lays claim to the uniqueness of American poetry by virtue of its origins in Native songs. “It may be,” Henderson writes, “that the folk-spirit is a necessary sub-soil for any fine national poetic flowering.” On recommending Sherwood Anderson’s “Mid-American Songs” for publication in 1917, Henderson described them to Monroe as deriving from his “Native American soil.… One can imagine the soul of an old Plains Indian reborn in Sherwood Anderson.”

Henderson was also a frequent intellectual goad to Monroe’s poetic sensibilities, which were Gilded Age as much as modern. Monroe was convinced of poetry’s value as a progressive force in society—in the sense that her friend Jane Addams promoted literature as a moral good. Monroe also believed in poetry’s value as artistic labor on par with the work of painters, sculptors, and composers, who were more frequently paid for their work and represented by cultural institutions in Chicago such as the Art Institute and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Monroe’s advocacy of poetry’s moral and civic values—along with her constant desire to expand her magazine’s audience—irritated Pound, who believed in the freedom of the artist and his work from the qualitative opinions of readers outside the small literary set that he valued. Poetry’s long-standing motto from Whitman, “To have great poets there must be great audiences too,” was ludicrous to Pound. Henderson often served as an arbiter between Monroe and others’ aims and egos (especially Pound’s), and Henderson could be frank and intimate with Monroe as no one else could. In a letter to Monroe commenting on Poetry for September 1916, she writes, “And, oh, Harriet, whatever you do—don’t speak of ‘boosting the art.’ It is dreadful. You can boost a magazine—but art is above and a part from all boosting.”

III.

Working closely with Henderson and Monroe in Poetry’s early years was the poet Eunice Tietjens, who started helping in the office after a few of her poems were published in the magazine. Many critics (Amy Lowell, especially) admired her work. Her poetry was also included in Monroe and Henderson’s important 1917 anthology The New Poetry. Tietjens soon became Poetry’s business manager, and eventually assistant and then associate editor. She worked for Poetry until 1938, when she and her second husband, Cloyd Head (a Chicago playwright), moved to Europe and North Africa. Like Monroe, Tietjens was an intrepid traveler. After a 1914 trip through Asia, Tietjens began wearing Japanese-style dress and writing verse influenced by Japanese poetry. In 1917 she traveled to France to write for the Chicago Daily News as a war correspondent. She was supposed to write “women’s stories,” but her articles were much broader; her vivid reports of American soldiers in the countryside, food shortages in Paris, air raids, and how French women endured the war reveal her ability to infiltrate a scene and provide intimate, nuanced details of daily life.

In her autobiography, Tietjens describes her experiences at Poetry in nearly religious terms. She felt a spiritual camaraderie with the women at the magazine—she adored and idealized “Lady Harriet,” as she called Monroe—and with the women of the Chicago literary renaissance more broadly. She experienced an artistic “awakening” at the apartment of writers Margery Currey and Floyd Dell, a couple at the heart of Chicago’s bohemian arts scene, which catalyzed Tietjens’s confidence in her own writing. In 1914, Tietjens pawned her diamond engagement ring from her first husband to help Margaret Anderson and Jane Heap publish the Little Review. Tietjens understood the economic and social restrictions placed on women that made pursuing a professional artistic career difficult, yet she was also sensitive to the more conventional appeals of marriage and family. When she took over Poetry’s editorship briefly in 1923 while Monroe was traveling in Europe, she wrote dotingly to Monroe about the women of the office, two of whom were pregnant: “All the staff and unborn babes are well, Marion, Susan and Mila. Jessica’s [North] baby is born and a son. I never knew so fecund an atmosphere.” Indeed, the memoirs, letters, and poems written by women affiliated with Poetry magazine show a strong sense of their community, as well as loyalty toward and veneration of Monroe.

IV.

Monroe was a mother figure to poet Marion Strobel, who established the Harriet Monroe Prize for Poetry after Monroe’s death with the inheritance from her father’s successful engineering company. With her wealth and social connections, Strobel was beneficial to the magazine’s survival during one of its hardest financial periods, in the 1930s. Like Monroe, Strobel could appeal confidently to the sense of civic duty among the magnates of Chicago—whom she knew—in order to find additional financial supporters to keep the magazine afloat.

Strobel became associate editor in February 1920, a position she gave up in 1925, when her two daughters were young, though she was always connected to the magazine in some capacity: reader, advisor, financial supporter. Eventually Strobel returned to the magazine when George Dillon resumed his editorship after World War II. They co-edited Poetry until 1949. Strobel had adored and mentored the much younger Dillon when he worked at the magazine briefly in his undergraduate days under Monroe. A glamorous figure, Strobel hosted social events at her home for the magazine, allowing the Chicago culturati to meet and mingle with visiting literary figures.

Strobel had a famous liaison in 1919 with William Carlos Williams, inspiring a volley of poems between them. Williams had come to Chicago to give a lecture and reading, during which he and Strobel had a passionate affair. The week was marked by violent rainstorms, which brought large waves on Lake Michigan outside Williams’s hotel; he worked these images into his longer poem for Strobel, “A Goodnight,” in the form of repeated exclamations, asking his lover to “Sleep, sleep!” Strobel eventually replied to the reiterated demand to “Sleep!” discreetly in her own poem, “After a Quarrel.” But apparently she took exception to Williams’s poem and to his suggestion, in a letter, that she had designs on his marriage. She had no such thing. Like Monroe, Strobel had little difficulty setting straight one of the “major men” of modernism. Her biographical note in The Bookman Anthology of Verse (1922) includes this description: “Just as the young men of today who write poetry do not adopt the long hair and open collar of the ’nineties, so the ladies do not languish in scented boudoirs. The new group of women poets is active, vivid, normal and keen. Marion Strobel is one of the most active of them all.”

V.

Many more women worked at Poetry in editorial positions after Monroe’s death in 1936 and through the 1940s and 1950s, including Amy Bonner, Jessica Nelson North, Geraldine Udell, Isabella Gardner, and Margaret Danner. Danner is a particularly notable presence in Poetry’s history because she helped to deepen the magazine’s representation of African American poets.

Danner worked as an editorial assistant at Poetry starting in 1951 and became assistant editor in 1956. She was encouraged in her work by editor Karl Shapiro, Paul Engle, and later Henry Rago. She had grown up on the South Side of Chicago, like her cohorts Gwendolyn Brooks and Margaret Burroughs, whom she joined in the famous poetry workshop run by Inez Stark Cunningham at the South Side Community Art Center. Poetry first published a series of four poems by Danner entitled Far from Africa in December 1952.

Affiliated with the Black Arts Movement, Danner moved to Detroit in 1959 to found Boone House, a community group for black artists and poets. In the early 1960s she became a member of the Baha’i faith, a commitment that emerges in oblique, intricate poetic expressions. Lace is a recurring motif in her work—from the lace of a christening dress, to the patterns of lace in the massive white-domed Baha’i temple in the Chicago suburb of Wilmette, to lacelike patterns of iron in the fences of New Orleans, built by slaves.

Danner’s position at Poetry was an important step in establishing her successful career. She was the recipient of many poetry awards and was a celebrated poet-in-residence at several colleges and universities during her lifetime. In 1959, when Danner won a fellowship to study African and French art in Africa and France, she was quick to write to the editor of Poetry, Henry Rago: “I especially want to tell you too, because I feel that the award helps a little to justify your giving me the important title at Poetry.”

One of Danner’s most anthologized poems, written during the years she worked at the magazine, expresses the difficulty of professional advancement for even highly accomplished African Americans. An early version of the poem displays the epigraph “Not really the elevator man at Newberry Library,” referencing Poetry’s office location at the Newberry. Through the language of protest, “The Elevator Man Adheres to Form” traces back the history of an “elevator man” through the history of slavery and wishes for stronger sympathies among African Americans at all levels. The speaker wants the elevator man to lift up the lowliest—not just those who edit a poetry journal on the top floor of the library.

Danner’s vision of unity and capaciousness is a striking counterpart to Monroe’s conception of the magazine’s editorial aim, which she called its open door policy. “The editors hope to keep free of entangling alliances with any single class or school,” Monroe wrote in an editorial published in the magazine’s second issue:

They desire to print the best English verse which is being written today, regardless of where, by whom, or under what theory of art it is written. Nor will the magazine promise to limit its editorial comments to one set of opinions.

By accepting poetry of all genres and subjects—rather than “adhering to form”—Monroe also opened the doors of Poetry’s actual office to a remarkable and influential range of women.

Liesl Olson is the author of Modernism and the Ordinary (Oxford University Press, 2009) and the literary history of Chicago, Chicago Renaissance: Literature and Art in the Midwest Metropolis (Yale University Press, 2017), winner of the Poetry Foundation's 2018 Pegasus Award in Poetry Criticism. She has been the recipient of fellowships from the National...

Bright minds dreaming elegant dance of songs,

word warriors in army of Harriot Monroe

leap high from binders of arrogant men

and paper blank walls of dark factories

with poetry magazine that glows bright

as torch in hand of Lady Liberty.