A Hard Turn

“There’s no clarity,” a gallery director said about my artwork. “It’s not visually appealing, either.” His words hit me, half traumatizing me and half pushing me to reflect on my writing and artmaking processes.

I turned to visual art in January this year. I wanted to make tangible things with my hands, as if to counteract the pandemic- and sociopolitically-caused helplessness in Hong Kong. A different medium, I felt, might turn things around.

Some of the early “art pieces” I made after I rented a work station at Hart Haus have become an extension of how I present my father and myself in Besiege Me, which includes poems that intentionally queer (well, in a way) a Chinese father-son relationship, while reconstructing his childhood and adolescence, as well as our daily exchanges. “Biased Biography of My Father” ends with the following run-on lines that drown me like a whirlpool every time I re-read them:

[my father is a man] who found the cinematic mafia’s way of gambling

so compelling he doubled the hit-hit-

split, who’s obsessed with the swift incision

of occasional winning, who scattered options

& defeat across a table so they looked

manageable, who studied the odds

the struts of getting it right, whose dice

the queen hated to toss, who tumbled to live

linearly, whose life, accordingly, concurred.

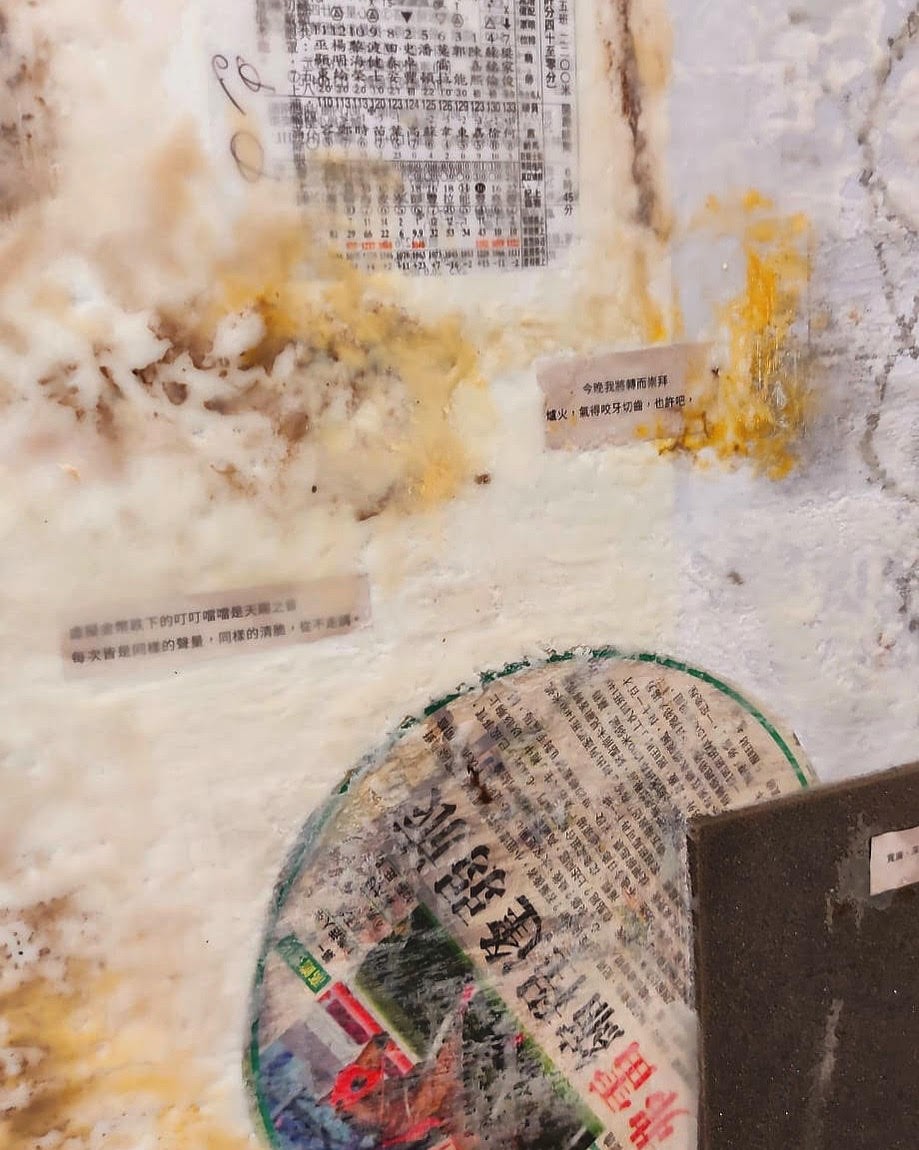

My father likes betting on horses for leisure. What a British colonial legacy! He usually does it twice a week, on Wednesdays and the weekends. He does his homework every time by studying the horse-racing papers. As far as I know, he loses more often than he wins. What interests me is that he usually makes minimal annotations on the papers when he watches the race live on TV. He lists his picks for every game next to a sophisticated-looking odds table. The horse-racing papers, this way, become his very own text type, and he, by annotating them, becomes a self-taught author.

Beeswax: my first serious medium since I joined Hart Haus. I found a broken board in a dumpster near my home. On it, I sealed clippings of my father’s annotations next to lines from my own poetry (sometimes I annotated them, too!) with beeswax. I liked the way the beeswax turned liquid and transparent at the mouth of my heat gun, the way I dipped my warmed brush into it, and looked at it turn white, solidify as it edged close to his text and mine, as if I were burying a father-son relationship beneath layers of frosting.

I carved a line from my poem called “Intergenerational” on the beeswax, then pigmented the words with an oil stick: “You asked me why I pulled out tissues / from a paper box as if from the center of you.” The violent shamelessness with which I keep hollowing my father (first in my poetry, then in my artwork) is tempting. I’m drawn to it. It stinks.

When the gallery director looked at the line, he commented, No idea why it’s in the form of a question. I wanted to tell him he just misread it. But he was right about one thing––there seems to be no straightforward clarity in my artwork. What should the eyes look at first? What next? And how can the visual cues in the work facilitate that? Are there visual cues, at all? I’m not surprised by his comment. After all, I did not have any formal art training, and he said what he had to say as the director of an art gallery, his perspective likely aligned with that of buyers. But I didn’t make the pieces intending to sell them, at least not at the beginning. I liked playing with the medium. I felt that my inner child had returned. I was searching for a way to “translate” my poetic work into another form.

I liked sticking things on a surface and scraping them off afterwards. I liked working on the same surface again and again. I liked building on it, over-saturating it with clippings, paper strips, words, various sorts of paint, then reworking the excess. I remove the excess, damaging it. There have been moments I feel sadistic in the whole process. That’s orgasmic. Very rarely do I have a picture of what I should make before I start with a blank surface. Like cruising, I sometimes keep working, waiting for accidents and mistakes to happen.

This very much resembles my poetry writing process. It’s taken me some time to realize that when I “translate” my poetic work into another form, I’m not doing it merely thematically. Instead, my artmaking practice is informed by my training in poetry writing: letting a draft build itself with language and clusters of imagery, then edit, edit, edit.

I don’t even know if I should be proud of it. This approach has entirely overlooked the significance of visual communication. My visual artwork, as a result, bears layers of accidental exposed and hidden parts. There’s not much emotion in it, a good friend of mine remarked.

Before the gallery director’s visit, someone told me to give him a copy of my new book as a gift. I had it ready, but I didn’t sign it, or write his name on the title page. When I was explaining the lines in my artwork, I asked if he read poetry. He said right away, No, not at all. An answer for a question. There’s nothing wrong about that.

Nicholas Wong is the author of Crevasse (Kaya Press, 2015), which won the Lambda Literary Award for Gay Poetry, and Besiege Me (Noemi Press, 2021). He is also the recipient of the Australian Book Review’s Peter Porter Poetry Prize. His translations have recently appeared or will appear in Ninth Letter, The Georgia Review, Colorado Review, Denver Quarterly,...