Digging Culture

The truth, so often obscured and omitted.

And I find I have much to say to my black children.

— Margaret Burroughs

About six months ago, I was digging through the record shelves of Beverly Records looking for classic jams. It is the kind of record store where, if you are lucky, you can fill out your collection with some of those deep cuts that make you think of a younger time when songs permeated your consciousness. It is a great spot to give your deejay record crate a little boost. I was looking for “And the Beat Goes On” as well as, “(Olivia) Lost and Turned Out” by the Whispers. I found a 12 inch of “And the Beat Goes On” but I was out of luck with “Olivia.” My official search was over. My friends were still knee-deep in vinyl at the listening station weighing the merits of The Chambers Brothers’ New Generation. I had time to satiate my other endless quest. For almost as long as I have been collecting records filled with songs, I have also been collecting records with no songs at all. It started with sounds that sparked my young mind, like tales of superheroes or soundtracks to animated feature films. In the last twenty-five years it branched out to tales of the Black experience, speeches, history, stories, and poetry.

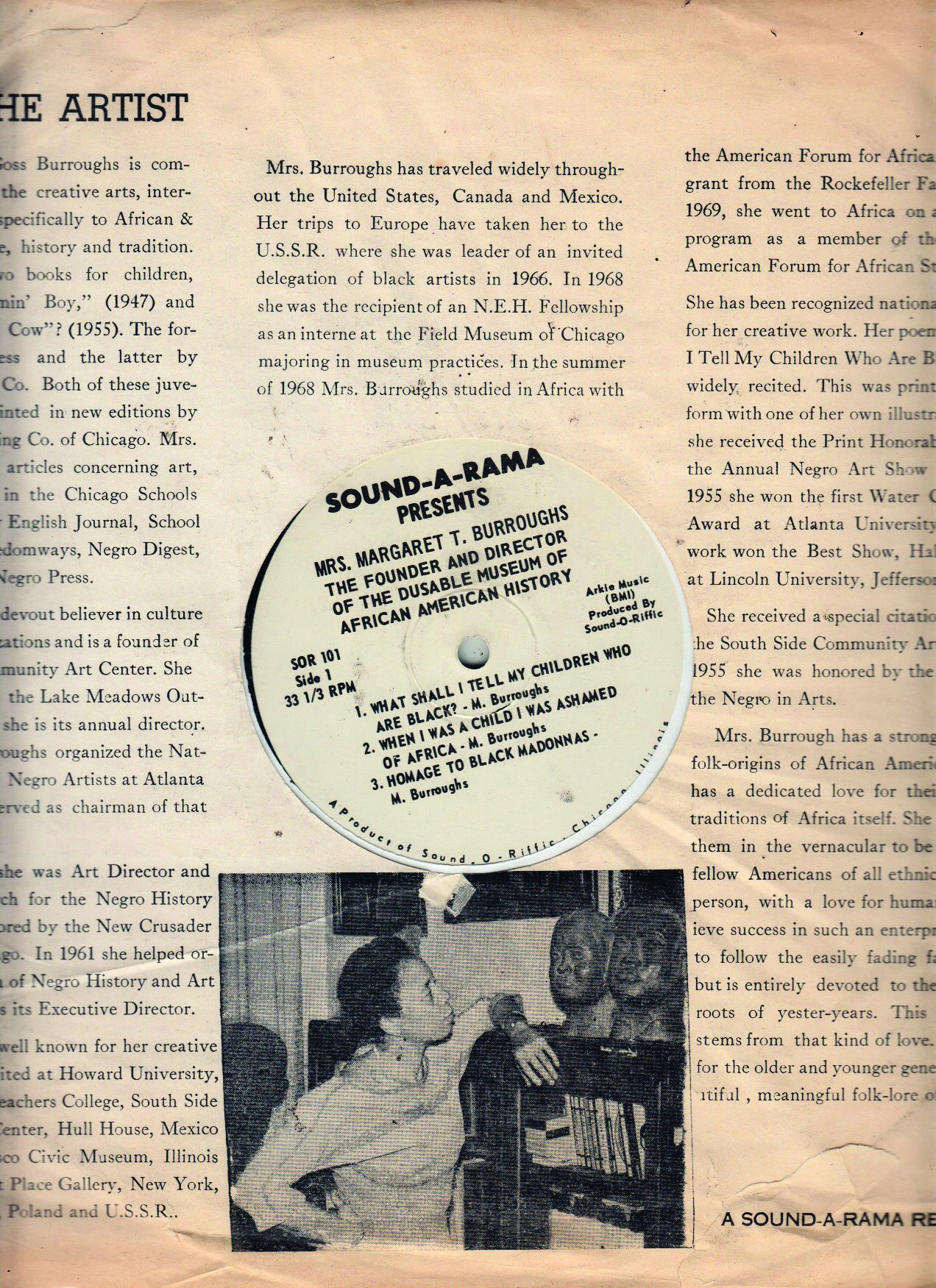

To find these records, you must go to the sections that are less frequently searched: the “spoken word” section. Beverly Records is a perfect place to locate a surprising gem. Certainly, few people are looking through the spoken word section in a “dusties” hot spot. I asked to be directed to the section. It took the folks that worked there a few minutes to find it themselves as it had recently been moved. The section was in the back and I had to stand on a chair to reach it. The tightly packed shelf was filled with the usual Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X records, and had multiple copies of the great three-volume set of Adventures in Negro History. I then pulled out a record without a sleeve. Inside the plastic sleeve that held the jacketless record, there was a xerox print of a woodcut of a woman with a little girl on her lap. The album was a recording of artist, educator, museum director, and poet Dr. Margaret Burroughs. It appeared to be a record of her reciting her poems from the collection What Shall I Tell My Children Who Are Black? (1968). I was thrilled. This is the kind of find that comes around very rarely. This record would not only have material that I would be able to use in one of my sound pieces, but was a piece of Black history that would be lost without this slab of vinyl. Burroughs did have a book of these pieces but to be able to hear her read them herself — those are moments, active, caught in perpetual audible revelation.

Dr. Margaret Burroughs, who founded the DuSable Museum of African American History and was a founder of the South Side Community Art Center. Dr. Margaret Burroughs, who worked tirelessly at Stateville Correctional Center teaching art to incarcerated artists. Dr. Margaret Burroughs, who has won too many accolades to mention here. Dr. Margaret Burroughs, an inspiration, someone who walked a path to uplift Black culture while the US actively oppressed it. Her voice is caring. She reads her words with confidence. Her tone is resolute. She sounds like someone I would like, someone I would like to ask about teaching art at Stateville, a job I do now. The poetry has an immediacy as the sound of her words hits the air. The past and present have no delineation. Her words speak to me. They help clarify work that still needs to be done.

As I prepare for an upcoming solo visual art show and several performances, I find myself listening to What Shall I Tell My Children Who Are Black?, realizing that I am one of those children (born in 1968). I feel an obligation to continue on with the work she and so many others put into play before me. Poems with the titles “When We Look at Ourselves” and “Let It Be Known” continue to stress Black self-empowerment. This time we are living in seems in so many ways as racially charged as when this record was made. Today, an affirmation is needed to validate Black life and it is still controversial. How will we survive this era? I wonder, what shall I tell the children now? Maybe I should play them this record.

And since this story is so often obscured,

I must sacrifice to find it for my children,

even as I sacrifice to feed, clothe and shelter them.

So this I will do for them if I love them.

None will do it for me.

— From What Shall I Tell My Children Who Are Black?

Damon Locks is a musician, visual artist, and educator. He works as part of P+NAP and the School Partnership for Art and Civic Engagement (SPACE) program for the Museum of Contemporary Art.

-

Related Authors

-

Related Collections

- See All Related Content