Explicit As a Star

In August 1950 Jane Freilicher received a letter from John Ashbery in which he recommended she read Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu. “One of Proust’s most exciting qualities,” the twenty-three year old wrote to her, “is the way he demonstrates how circumstances of one’s life which seem casual and ephemeral can solidify for the rest of one’s life (i.e. Swann’s relation with Odette).”

His prescience is amusing. He had met Freilicher — as he put it, “a pretty and somewhat preoccupied dark-haired girl” — because she shared a kitchen in the same apartment building on Third Avenue near 16th Street with Kenneth Koch, a friend of Ashbery’s from Harvard. Koch, visiting his parents in Cincinnati for the summer, had sublet his apartment to Ashbery, and Freilicher let him into the building. The two were, as Koch put it in his later poem “A Time Zone,” immediately “Afloat with ironies jokes sensitivities perceptions and sweet swift sophistications.” Writing six years later to Harry Mathews, Ashbery explained, “She [Jane] is probably my favorite person in the world . . . Also everything she says is screamingly funny, although she doesn’t seem to intend it that way and I am always getting her in hot water by laughing at her gags in the presence of people who don’t seem to have noticed any humor going on.”

Jane Freilicher in The Automotive Story, 1954, dir. by Rudy Burckhardt (film still).

On meeting Ashbery, Freilicher took her new friend along to the first day of shooting of a film by Rudy Burckhardt, and they both ended up starring in Mounting Tension (1950), along with Larry Rivers and Ann Aikman. The production is a comic, improvisatory enterprise, instinctively tongue-in-cheek in its representation of romance and modern art. Halfway through, we first see Freilicher sitting at her desk with her feet up on the table, reading a detective story, with a portrait of Freud and a stuffed alligator hanging on the wall behind her. This is Madame Frauhauf, a psychoanalyst and solver of problems, who advertises by way of sandwich boards worn by unhappy-looking men.

Hearing Rivers’s footsteps on the stairs, Freilicher hides her book, strikes a pose, and sashays across the room to greet him. She is smart and restless, a moll in gainful employment, charmingly assured; first, she adjusts Rivers and his sexual frustrations by a talking cure, then by sheer quackery, and finally by seducing him. Ashbery plays the part of the jock boyfriend, resentful of Aikman’s sudden enthusiasm for modern art. The two arrive in Madame Frauhauf’s office for couple’s counseling — only to find Rivers there who is, by chance, part of their problem; he had previously tried to bed Aikman in his painting studio, showing her various female nudes and waggling his eyebrows in such a way as to suggest a certain logical inevitability. Ashbery and Rivers chase each other around Madame Frauhauf’s office trading blows, the four actors visibly stifling grins. Burckhardt then cuts abruptly to the final scene, in Central Park, where the couples have swapped for no good reason and harmony has been restored: Aikman rows on the lake while Rivers plays his saxophone, and Ashbery paints Freilicher on the bank. It’s a Parnassian vision undercut by the senselessness of events: the characters have literally wandered into each other’s lives off of the streets of Manhattan, and that which is casual and ephemeral has been committed to celluloid. Freilicher turns her face to the sun, smiles, and arches her back, and we see for ourselves the truth of O’Hara’s description of her in his poem “To Jane” as a “slightly thoughtful, smiling Jane.” We see the same look in photos of her at the time, and in her portraits of women — a cheerful look of inward preoccupation. She alone knows what she is doing, and isn’t sure what all the fuss is about.

Freilicher showed the same confidence as the pseudo-host of Burckhardt’s movie The Automotive Story (1954), filmed three years later. The film begins with her sitting in a living room, one leg crossed over the knee, leaning forward, twisting a large white chrysanthemum between her hands, and confidentially imparting her name — Marjorie MacManus. She is, she says, going to tell us a few things about cars. She smiles; the camera moves in close. “Who are these messengers?” she asks, half mockingly. “From where do they come?” She marvels with such exaggeration, equal parts plaintive charm and condescension. Just as in Mounting Tension, she is playing the part of the professional. She wears pearls, and her dark hair frames her face. Burckhardt cuts to scenes of cars driving in New York City, but her voice — reading the script written by Kenneth Koch, pausing for music played by Frank O’Hara — continues.

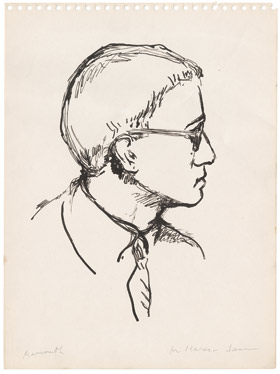

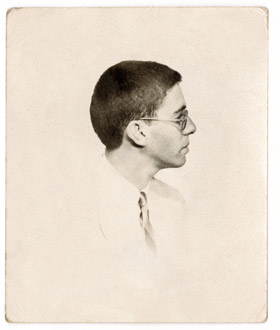

left: Portrait of Kenneth Koch, undated, ink on paper, 12 × 8¾ inches. Private collection.

right: Photograph of Kenneth Koch. All artwork by Jane Freilicher unless noted otherwise.

Freilicher’s performances in Burckhardt’s films are some of the few pieces of direct evidence that attest to her remarkable presence in the circles of friendship and acquaintance that have been given the entirely too-formal name of the New York School. In the distinct coterie that formed around the Tibor de Nagy Gallery in the early fifties — which drew in artists like Rivers, Grace Hartigan, Alfred Leslie, Robert Goodnough, Nell Blaine, and Fairfield Porter, along with the poets Frank O’Hara, James Schuyler, and Barbara Guest, in addition to Ashbery and Koch — Freilicher occupied a singular position, inspiring an unparalleled devotion among her friends, particularly the poets. Quite simply, she was famous for her wit. A visit with the composer Virgil Thomson was like being “locked in the office with the school principal.” Robert Motherwell and Helen Frankenthaler, having married, were now “the Irene and Vernon Castle of Abstract Expressionism.” Her letters were frequently passed around; as Ashbery noted, they were considered “required reading in my set.” In his classes at the New School, Koch was inclined to make analogies between painting and poetry, elaborating, as Bill Berkson recalled, on “the amplitude of a de Kooning, Larry Rivers’s zippy, prodigiously distracted wit, or Freilicher’s way of imagining with her paint how the vase of jonquils felt to be on the window sill in that day’s light.” For Koch, Freilicher’s sensibility was a crucial part of the New York School’s influence. An appreciation of her tone even became a marker of taste: James Schuyler, Koch later recalled, “passed one test for being a poet of the New York School by almost instantly going crazy for Jane Freilicher and all her works.” Schuyler wrote a short play about her, Presenting Jane, which John LaTouche filmed in the summer of 1952, when they all rented a cottage in East Hampton on Long Island. The footage is now lost, but it apparently featured Freilicher walking on (or in) very shallow water. “Poor Jane was constantly up to her ankles in slimy mud,” recalled John Bernard Myers, then director of Tibor de Nagy Gallery.

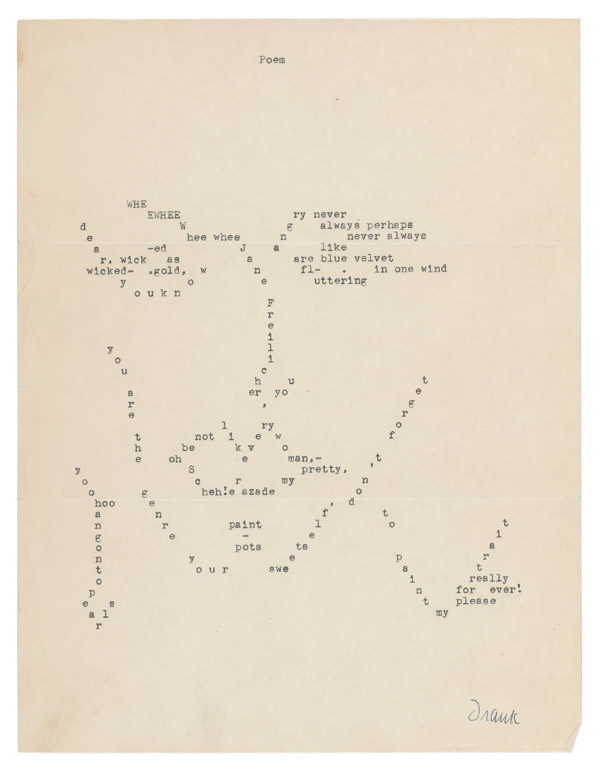

That same summer, Rivers was also staying out at Southampton, and he wrote a paean to Freilicher — an eight-page eclogue in which Ashbery, Koch, and Rivers take turns to praise Freilicher, who “fears beauty like a nun,” whose “silent power is rooted in reason,” who is “blessed with a brain” — a “queen who holds her court.” The last line in the poem is Freilicher’s voice, calling out to them: “John, Kenneth, Larry, / I have the coffee set.” There are many unpublished poems like Rivers’s in Freilicher’s papers, which are held at the Houghton Library at Harvard University. O’Hara, for instance, wrote a poem-portrait that was literally shaped to resemble her face. Koch, Ashbery, and Porter each wrote poems that were either about her or dedicated to her. “Jane thinks poems should end,” Koch writes, “not with a bang but a whimper; / The quiet demise of a thought she’d defend / As the meter gets limper and limper.” The massed intensity of these poems — no matter how much they verge on doggerel (or perhaps because they do so) — is the most persuasive indication of Freilicher’s effect on others. She inspired the gift of attention — uncritical, adoring attention. Freilicher would be the first person to admit herself nonplussed by the cause of this to-do. Unlike other painters, she did not directly collaborate with her poet friends, sitting down to make lithographic prints like Rivers and O’Hara did together for Stones (1960), or taking a poet’s words and including them in a painting, as Hartigan did with O’Hara’s “Twelve Pastorals” in her Oranges series (1952). Though Freilicher designed book covers and sets for plays, and contributed artwork to books of poetry, her images all have an accommodatory feel, as if she were making room for the poet, helping to stage their words rather than creating any kind of third mind. For instance, the landscape drawings she did for Charles North’s poetry collection Elizabethan & Nova Scotian Music (1974) are modest and casually beautiful. The house she drew for What’s For Dinner? (1978), Schuyler’s third novel, seems simply designed to express the comforts of a well-appointed home. In this collaborative work, she is setting the tone, but not the subject.

“Poem (WHE EWHEE),” by Frank O’Hara, undated. Reproduction of the original in the Jane Freilicher Papers, MS Am 2072 (50), Houghton Library, Harvard University.

O’Hara and Freilicher’s friendship is a particularly good instance of the ways in which passionate regard led to art. Among others, O’Hara wrote the poems “Interior (With Jane),” “A Sonnet for Jane Freilicher,” “Chez Jane,” “Jane Awake,” “Jane Bathing,” “Jane at Twelve,” and “To Jane, Some Air.” Many of these were characterized by pleasurably baroque visions of possible lives and transformations — in “A Terrestrial Cuckoo,” O’Hara imagined the two of them in a canoe “paddling up and down the Essequibo.”

The poem ends:

To return with absolute treasure!our only penchant, that. And a red-billed toucan, pointing t’aurora highlandsand caravanserais of junk, cries out“New York is everywhere like Paris!go back when you’re rich, behung with lice!”

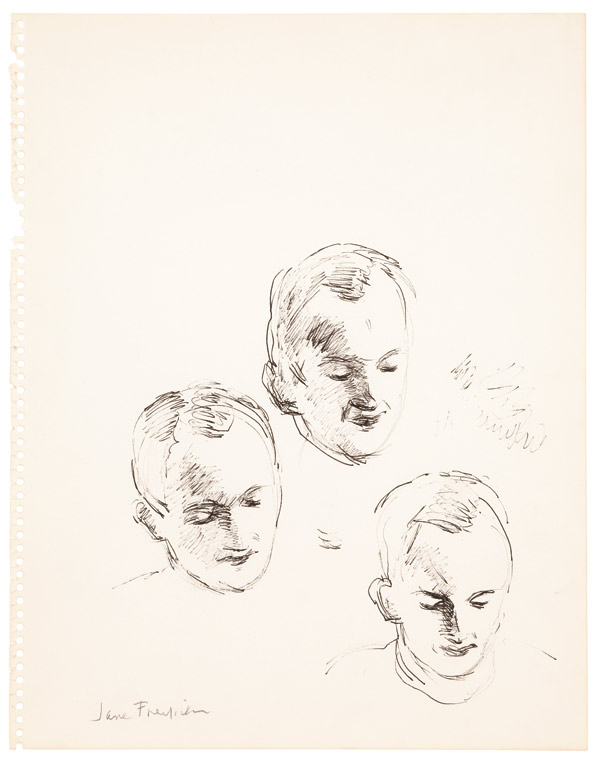

Untitled (Frank O’Hara), undated, ink on paper, 14 × 11 inches. Collection of Jonathan Galassi.

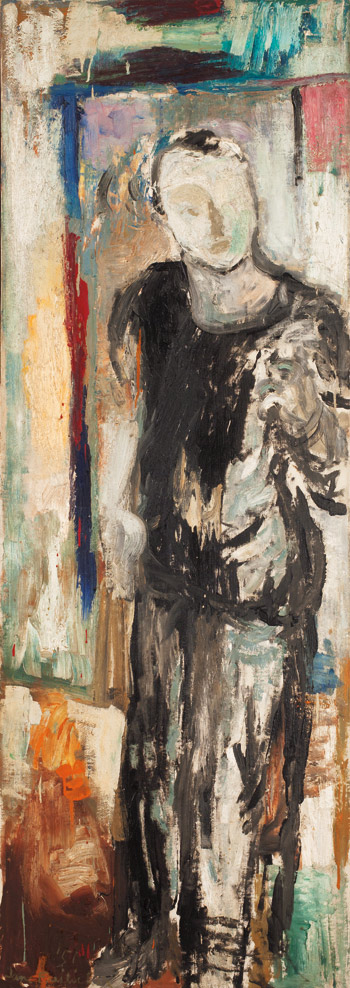

Frank O’Hara, 1951, oil on linen, 65 × 23 inches. Collection of J. Philip O’Hara, Providence, Rhode Island,

and Ariel Follett O’Hara, Deerfield, Illinois.

Freilicher visited O’Hara in Ann Arbor, Michigan, the following year. She painted his portrait, capturing his characteristically tilted neck, the sway of his body. The joys of portraiture were mutually constitutive; Freilicher and O’Hara helped each other to form a distinct aesthetic point of view. After her departure back to New York O’Hara wrote and commented that her portrait of him, hanging over his desk, “has gotten to be very good to my habitual eye.” An earlier version, he thought, “was merely the discovery of the image.” The casual authority of O’Hara’s tone here was an augury of the art writing and curatorial work he would later do in New York. In the same letter he recommended she read Paul Goodman’s latest essay in Partisan Review, in which Goodman argued that the key task for any member of the avant-garde was to make art for and about one’s friends. The essay was, he wrote, “really lucid about what’s bothering us besides sex, and it is so heartening to know that someone understands these things.” He drew a portrait of her below these typed lines, demonstrating very simply, almost accidentally, Goodman’s theory in action.

Of course, ardent theorizing about the aesthetic importance of one’s friends is practically a stage of development in the psychology of any avant-garde art movement, and one shouldn’t read too much distinct significance into, say, O’Hara’s echoing of Proust in his inscription on a movie poster for Cocteau’s Orpheus, which he sent to Freilicher. (Above the blue pen-and-ink portrait of John Marais and Maria Cesarès, he wrote, “You and I à la recherche du temps perdu.”) It’s easy, after all — particularly for a quick and ambitious artist — to see the world in your own image. And Ashbery’s courting of Freilicher’s approval in his letters to her in the early fifties is sweetly palpable. Very unusually for Ashbery (then, as now), he asked Freilicher’s advice on his poetry, crossing out words in the last line of a poem that was then titled “Two Promenades” and writing in cursive below: “As you can see, I’m uncertain about the last line. What are your views? Is it clear that it’s ‘faith,’ not ‘their light’ which is explicit as a star?”

He regretted sending her earlier versions of the poem; as he put it in a postscript: “(a) I have a natural horror of letting people see how my mind works and (b) the poem is difficult to complete when one no longer has the prospect of charming one’s friends with something completely new.” The sweet confidences that come from sharing one’s private aversions: there is no better indication that the universe of a friendship is being created, the gases of thought circulating and expanding in swift escalations of intimacy. Yet if you thought about it for very long at all, you might find it absurd to assume that just because Freilicher and Ashbery were friends, their aesthetic influence on each other was somehow singular. Freilicher herself, in an interview, described her friends’ influence as “indirect.”

Look at a distant star directly and it disappears; look at it from the corner of your eye and it reappears, a faint prick of light. The same summer that Rivers wrote his eclogue about Freilicher, and Freilicher tolerated shallow water and muddy ankles for art, Schuyler and Ashbery, in the back seat of a car driving back from Southampton to New York City, began to pass a notebook back and forth, writing alternate sentences of a story that would become their collaborative novel A Nest of Ninnies. The novel’s first sentence — ironically enough, given their location — is spoken by twenty-something Alice Marshall, who stares into her own eyes in the mirror above a mantelpiece as she says, “I dislike being fifty miles from a great city. I don’t know how many cars pass every day and it makes me wonder.” Driving past houses exactly like Alice’s, Schuyler and Ashbery were calling on their shared history with “the outer suburbs.” As Schuyler later wrote to Clark Coolidge: “Certain things about his mother and her house, and my mother and her house are strangely (?) alike — as a glance in their respective china cupboards would plainly show.”

It was these china cupboards — and the question of what they represented when it came to issues of aesthetics and art — that delighted Ashbery and Schuyler in chapter after chapter during the sixteen years it took to finish the novel. A Nest of Ninnies satirizes any Modernist notion of creative exile by carefully documenting the minutiae of middle-class travel aspirations of characters who meet over cocktails and at dinner parties, first in the commuter suburb of Kelton, then in New York, Florida, and finally in France and Italy. The characters’ conversations rarely turn to contemporary events, politicians, writers, or artists. Rather, the main vehicle for satire in A Nest is taste — and the novel’s humor comes from “tasteful” habits, such as the peppering of one’s speech with French phrases. Cultivation is measured by how one decorates one’s home with the spoils of one’s sorties in Europe. Alice and her beau, Victor, even decide to open a “notions shop,” which is intended to be a cut above the rest. Their conversations about what to include are pricelessly precious:

“Well,” Victor said, “you see, we’re trying not to specialize — like French copper-bottomed pots, for instance. On the other hand, we are trying to play down Japan a little.”

“And what’s more,” Alice boomed with unexpected gusto, “we feel it’s time the Western Hemisphere had its day in court. Besides Guatemalan rebozos, we’re getting some Eskimo walrus-tooth accessories and some Navajo turquoise and silver jewelry that’s not the usual junk.”

Jimmy Schuyler, 1965, oil on canvas, 30 × 24 inches. Courtesy Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York.

The comic intensity of Schuyler and Ashbery’s collaboration came from the splitting of cultural hairs. Even if you were making fun of it, matters of taste were of slight but crucial distinction. The humor of A Nest was so particular that in their letters to each other, Ashbery and Schuyler applied the novel’s title to all kinds of behavior; one could do “a little Ninnying”; one could be “very Nest.” Chapters, as they were completed, were distributed among friends. Fifteen years later, when she had finished reading the full book, Freilicher wrote to Schuyler and remarked, “I feel I have sat for quite a few life studies in it, especially Fabia Bridgewater. But I guess that’s what accounts for its profound universality. Gosh you boys are clever! A gold mine of silliness, that’s what it is.” (Fabia, a young woman with no small amount of moxie, is fond of speaking what’s on everybody else’s mind, especially if they don’t wish to remark on the matter out loud.)

In a way, although the circumstances of their friendship in the early fifties, so “casual and ephemeral,” as Ashbery noted, is the grounding force for a portfolio like this one (a narrative for which anecdotes have become apocrypha), it was succeeded by another kind of rhythm and circumstance that developed into the sixties and seventies — a rhythm inferred by A Nest of Ninnies’s composition, focus, and reception, and just as significant as those first heady years of gallery openings, parties, and films. It’s this later, middle-aged existence, just as casual, that has quietly become a foundational aesthetic force in Freilicher’s life. W.H. Auden called A Nest of Ninnies a “minor classic” — minor, that is, in a calculated way (just as O’Hara, for instance, might insist that Les Sécheresses by Poulenc was better than Tristan und Isolde). This art did not shock in the way that Pollock’s all-over drip paintings or Warhol’s Brillo boxes might, which, at the time, were the go-to figures in Ashbery’s art writing for the apparent avant-garde.

Interior, 1955, oil on linen, 60 × 44 inches. Collection of Elizabeth Hazan.

In 1968, as Schuyler and Ashbery were working through the proofs of A Nest of Ninnies, Ashbery spoke at Yale University on the question of the avant-garde, and began by noting that the invitation to speak at the college was itself an eloquent characterization of how swiftly risky art was now being absorbed and accommodated by the mainstream. “It might be argued,” he wrote, “that traditional art is even riskier than experimental art; that it can offer no very real assurances to its acolytes, and since traditions are always going out of fashion it is more dangerous, and therefore more worthwhile than experimental art.” This traditional turn has a great deal of consonance for Freilicher’s painting over the years. In the late forties and early fifties, the dominant abstract expressionist mode in downtown painting made its way into her brushstrokes, but her subjects were still recognizable; for lack of a better term, her sense of the figure recalled a painting tradition others seemed intent on reinventing altogether. Her interiors are just that — portraits of a room in which each object is treated with the same loose detail. In Interior (1955), lilacs hang down with the same weight as a blue shirt draped over the back of a chair. The purple and green walls, the whitened lines of the doorframe, window frame, and shelves, all press forward gently, up against Freilicher’s possessions. The colors and the way they are mixed give these early paintings the look of a faded world. As Porter noted in his review of her first show at Tibor de Nagy Gallery in 1952, it appeared that Freilicher was “trying to rediscover first principles. Her painting is traditional and radical. She is consciously imitative of the masters of the Renaissance, but in a first-hand way.” In her landscapes, individual lines gave contour swiftly and simply, acting as the treble, the melody of the composition. The line of a roof, of a hilltop, of a bank, separated the world into elements: house, land, sea, and sky.

Grey Day, 1963, oil on linen, 24 × 32 inches. The Parrish Art Museum, Water Mill, New York. Gift of Larry Rivers.

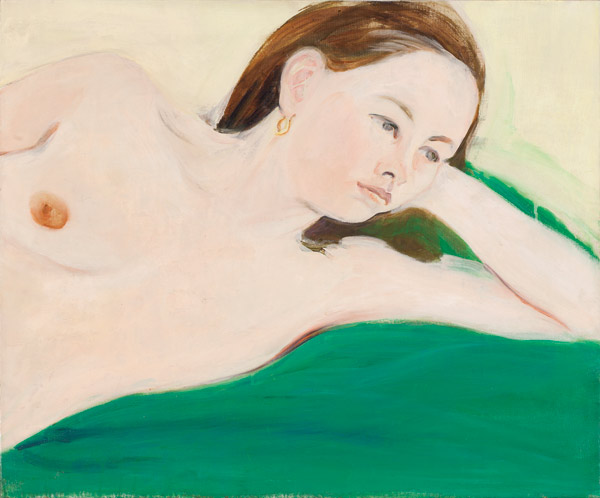

Nude on a Green Blanket, 1967, oil on linen, 25 × 30 inches. Courtesy Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York.

This sense of singularity only increased throughout the fifties. By Grey Day (1963), Freilicher was increasingly allowing her colors to separate rather than blend; the pink apricot streak on the far shore in this painting has no echo. Looking at this painting one senses, quite clearly, that the world is being resolved as a painting, along with her willingness for us to see the terms of this translation. The syntax of her painting — the formal elements of line, wash, the thickness of her strokes — was becoming clear. Each painterly gesture is presented so distinctly in Woman in a Photograph (1963) that we sense an instructive force. And in her nudes there was a growing pleasure in the intensity of color — a tendency that was matched by Porter’s own appetite for color in his paintings of domestic interiors. In Nude on a Green Blanket (1967), the green blanket she’s resting on is a pleasure to look at because it is so strong a visual element. The color has its own shape, its own upward motion that balances the model’s own weight pressing down. In the pool of pink skin, the brown nipple has as much presence as the lips; each line hovers as democratically as contour lines on a map. The eyebrows and eyes are as succinct as the rooftops in Grey Day. The musculature is as faint and distinct as a thought.

On the one hand, these changes are most likely an indication that Freilicher, moving from her late twenties into her thirties, was coming into her own as a painter. But there were other more specific events that aided this sense of consolidation. In 1952 Freilicher met Joe Hazan, whom she had first seen in Burckhardt’s film The Dogwood Maiden (1949). (Hazan, in turn, had first seen her in Mounting Tension.) They married five years later, and moved first into a house at 16 West 11th Street, then later into a penthouse apartment nearby on Fifth Avenue. Hazan was working in the family sportswear business and they regularly spent summers out at Southampton, in 1960 building a house in Water Mill, overlooking Mecox Bay. “If one were to describe my early twenties,” Freilicher recalled in interview, “it might be called after Thomas Mann’s story ‘Disorder and Early Sorrow.’ I’ve grown into a certain amount of maturity.” There is the distinct sense from letters, interviews, and her own work that Freilicher settled into an increasingly domestic routine, dividing her time between Long Island and Manhattan, and, in 1965, giving birth to her daughter, Elizabeth.

These events — marriage, a series of new homes, and a child — are usually considered distractions to women artists, hindrances to their careers. But for Freilicher they became the wellspring of her invention. As Ashbery wrote of Freilicher in 1984, “After the early period of absorbing influences from the art and other things going on around one comes a period of consolidation where one locks the door in order to sort out what one has and to make of it what one can.” It is a “question,” he wrote, “of conserving and using what one has acquired,” of “having to live with the pleasures and perils of independence.” The rhythms of her daily life allowed for a new depth, a quickening of her skill, because she focused, over and over again, on capturing the interiors of her apartment in Manhattan and home in Long Island, along with the view of the city or countryside beyond. The views are not spectacularly dramatic or glamorous; the water towers in her New York skyline are quietly identifiable and the fields and estuary seen from her windows in Southampton are prosaic, an undistinguished rural setting occasionally interrupted by houses in the distance. But the extremity in her art came from her commitment to these views. In 1975 she was commissioned by the Department of the Interior to paint “the American scene” and was offered a trip anywhere in the United States to do so — but Freilicher chose to paint another view from her home. “I have to feel comfortable where I am,” she noted in an interview. “I have to burrow in and feel at home.”

Loaves and Fishes, 1972, oil on canvas, 42 × 38 inches. Private collection.

Twelfth Street and Beyond, 1976, oil on linen, 50 × 60 inches. Private collection.

It’s worthwhile considering what this sense of home contained as time passed and she matured as a painter. Consider, for example, Loaves and Fishes (1972). Though much of the composition is an exercise in whites and grays — the silvery fish, the white tablecloth, the white china plates, and sprays of baby’s breath — she uses touches of color so accurately, so precisely, that no small part of the pleasure in this painting comes from our recognition of the differences between the objects on the table. The fish are luminous, slippery with death, and the loaf glows red and brown, like an animal. The marigolds are pleasurably bushy, awkward, and well meaning. Behind them, underneath them, there is a vase, the green of an old glass sea float. The painting seems pearlescent. Whereas her earlier paintings presented one thing, a resolution of view, Freilicher is playing here with the tension of parts, of keeping things separate, even enhancing their degrees of difference. In Twelfth Street and Beyond (1976), the red sheet on the table is unabashedly strong, and the greens of the potted plant, the blue china jug and mug push brightly against each other, optimistic and fierce, just as unconcerned and confident as the detailed cityscape outside the window. The force with which each object balances another is almost audible, like the low hum of a transformer in the country. The painting is pellucid. The same clarity extended to her landscapes. The marsh grasses, the lawn, the individual striations of clouds, the detailing of houses in the distance all took on a confidence, a springiness. The yellows became more golden, the blues deeper. In Summer of 72, the blackbirds caught on the wing over a cornfield have an accuracy so pressing that we almost see the ghostly referent behind the painting, the view as it might exist in a photograph.

Summer of 72, 1972, oil on linen, 53 × 68 inches. Private collection.

Of all the poets in Freilicher’s circle, it is Schuyler whose poetry most closely resembles Freilicher’s painting in terms of subject and approach. He also divided his time between Southampton and New York; from 1961–73 he lived in New York City, at Fairfield and Ann Porter’s home in Southampton, and frequently summered at their family cottage on Great Spruce Head Island in Maine. He wrote about the views from these homes — and the friends that visited — repeatedly. In “June 30, 1974,” for instance, the narrator is enjoying being the only one awake in a house full of friends. The poem ends:

Enough tosit here drinking coffee,writing, watching the clearday ripen (sucha rainy June we had)while Jane and Joesleep in their roomand John in his. Ithink I’ll make more toast.

Schuyler’s anticipation is daily, modest. The house, he notes, is “alive with paintings.” Their shared taste is emphasized. Yesterday, he writes, “she / and John bought / crude blue Persian plates” — plates that could have quite easily turned up in one of Freilicher’s paintings.

Schuyler was also fascinated with flowers and color, in tracing the narrowing of visual focus. Consider the ending of his poem “February,” in which we move from inside a tulip to the day beyond, sensing the shapes of objects in the world around us, the way they take up space — and in turn, the way we take up space. There is also an exact focus on the relationship between parts in a coherently unified scene:

It’s the yellow dust inside the tulips.It’s the shape of a tulip.It’s the water in the drinking glass the tulips are in.It’s a day like any other.

Schuyler and Freilicher’s aesthetic similarities may have more to do with Porter and Schuyler’s friendship — and Porter’s domestic interiors — than anything else. And any commonality could be put down to broader and deeper currents in the art and poetry world. For instance, despite Schuyler and Freilicher’s care with the visual coherency of flowers, neither had any interest in being held to any standard of empiricism. Freilicher did not sketch her scene onto her canvas before painting, and she commented in an interview that a painting’s composition only resolved itself as she painted: “I might plunk down a number of vases, or some flowers, or some stuff, in a window, and add the window. I sketch around it, not really knowing what’s going to happen. At a certain point, I have an idea, and then I have to resolve it. Sometimes the resolution is bumpy. It’s sort of like moving furniture in a room where you think you have it and then you find it’s all wrong.” This sense of arrangement and rearrangement, of moving in close then standing back — the slow resolution of an “idea,” a thought, or a mood — is a nice description of the creative process involved in any composition, musical, visual, textual, or otherwise. The focus was on capturing how one saw the world, with all the attendant phenomenological twitches and adjustments that this process implied. O’Hara noticed this then when he wrote that her “responsibility seems to be her perceptions rather than to painting,” as did Schuyler, writing in one review of her work that “the emotional force of an object is allowed its compositional weight . . . Structure is an improvisation, composed as painted, not a skeleton to be fleshed out.” In his poems, Schuyler was just as attentive to correcting his perception, in tracing the movement between the unplanned, the observed, and the invented. This attentive improvisation is not so unusual among painters and poets, but the similarity between Schuyler and Freilicher (and Porter) became more pronounced given their shared subject matter. Looking at Freilicher’s Southampton paintings in the eighties, we can easily recall Porter’s assessment of Schuyler’s poetry as offering “a deceptively simple Chinese visibility, like transparent windows on a complex view.”

Theme and Variations (The Painting Table), 1986, oil on linen, 53 × 68 inches. Private collection.

As time passed, the pleasure of Freilicher’s watching had only become more playful. Increasingly she was willing to allow the details of the house itself to be part of the view — the glass doors, the punning framing of the window frame and picture frame, the quiet joke of the curtains (as in Theme and Variations [The Painting Table] ). Sometimes it’s unclear whether the view we’re seeing is the view outside her windows, or if she’s placed a bunch of flowers in front of one of her paintings. There is a questing quality to their oddness. In Flowers and Mirror Before a Landscape (1983), the mirror, leaned against the corner of the window, allows us to have eyes in the back of our head, to see behind ourselves. Their gentle joking magic is undercut by the occasional presence of bulldozers and plowed fields; at the time, developers had beset Mecox Bay.

Flowers and Mirror Before a Landscape, 1983, oil on canvas, 75 x 85 inches. ExxonMobil Collection, Irving, Texas.

The city paintings, painted at the same time, contain a different sense of experimentation. On the one hand, they seem more traditional, less interested in perspectival pyrotechnics. But each object has gravity, a weight that the plants in her landscapes do not have. The grasses outside are content to be there, to hug the ground close, but the flowers in her vases in Manhattan are always moving upwards, often reaching up and out of their container. In the beautifully named Parts of a World (also the title of one of Wallace Stevens’s collections of poetry) we sense the city schematically conveyed in terms of a still life: four fish on a black plate, two other dishes (one gray, one china blue), a small statue, a pink orchid. The objects on the table get on comfortably enough, though we cannot entirely be sure of the intention of the arranging hand in all of this. The cityscape behind is equally impressive — all of that detail, all of that light.

Parts of a World, 1987, oil on linen, 68½ x 53 inches. Courtesy Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York.

Everything is closer than we would expect. We are made aware of the intricacy of the scene, of how technically good Freilicher has become, and we are aware that there is a lot to take in in the world. These are paintings that notice a lot, but that skill dissolves, becomes invisible, in patches of enjoyment.

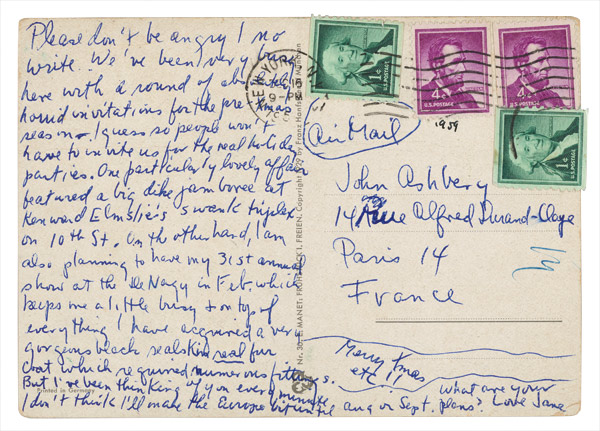

Postcard from Jane Freilicher to John Ashbery, December 16, 1959. Reproduced from the original in the John Ashbery Papers (AM6), Houghton Library, Harvard University.

It’s these paintings, with their sense of casual intricacy and occasionally dissolving quality, that remind me more of Ashbery’s poems. Schuyler, Freilicher, and Ashbery were very aware of the natural complexity with which a vase of flowers staged a false divide between nature and artifice: that subtle disconnection of cut blooms. But Ashbery, more than the others, was skeptical of their function — or at least, hyper-aware of their sociability. (It’s no coincidence, I suspect, that Ashbery sent her two postcards, years apart, that were from the same series, Langage des Fleurs. “J’aime la violette,” he wrote on one, and on the other, “le géranium rose. Retournez-moi votre fleur préférée.”) In his poetry Ashbery uses flowers as rhetorical devices rather than lingering on their visual appearance. In “The Ice Storm,” the poet comes across a rose in the garden that was, he writes, “doing what it was supposed to do — miming freshness tracked by pathos.” The quickness of his assessment here has its own lyricism, but it does not come from our imagining the flower itself. He is a poet of movement. If color intrudes, it does so as a flash, rather than something to linger on, as in “Whatever It Is, Wherever You Are”: “The tendrils can suggest a hand, or a specific color — the yellow of the tulip, for instance — will flash for a moment in such a way that after it has been withdrawn we can be sure that there was no imagining, no auto-suggestion here, but at the same time it becomes as useless as all subtracted memories.” Porter described Ashbery’s poetry as “opaque; you cannot see through it anymore than you can see through a fresco.” There is this opacity in Freilicher’s sense of dissolution in her paintings in the eighties: the roundness of a setting sun like a copper penny, or the uncannily accurate isometric sketching of a cityscape, set out on the frank non-space of terracotta-colored paper.

Like a shout across a body of water, we cannot trace these echoes back to their source, nor would we really want to. Maybe it is enough to suggest that the three shared a taste, a gentle desire for very similar kinds of art, as well as for a gracious existence composed of the pleasures of the good life: beautiful things, fine food, excellent company. It’s this sense of commitment to pleasure that seems so consonant with Ashbery’s and Schuyler’s quiet amusement in A Nest of Ninnies. Freilicher traveled three times to Europe in the sixties, and on each occasion visited Ashbery, then living in Paris. In 1962 they traveled through Sicily, Barcelona, and France, and in 1964 they drove through France and Spain to Morocco with Joe Hazan and Larry and Clarice Rivers. These two trips — the rambling, ambitious Grand Tour — are precisely the kind of trip made by the characters in A Nest of Ninnies. The novel is a ghostly echo of real lives and, in that sense, constructs a kind of shared ground against which we can place their friendships. We could well ask what this parallel implies, especially if the novel contains a deliberately flattened sense of psychological interiority; what, for instance, separates Paul Lambert — a character who enters exuberantly into the novel, as “a dark heavyset man of thirty-eight, with busy but receding hair” and who roars “Well, Victor. . . at last we meet!” — from Harry Mathews, the writer on whom Lambert’s appearance, manner, and hobbies were based? A Nest of Ninnies’s refusal to engage in conventional interior “depth” suggests an anxiety, or at least a question to which there is no easy answer — and this question, it seems, is about that decorative sensibility which is accepted by all characters as sufficient grounds for contentment. In a way, the characters’ uncritical pursuit of the ornamental, their time spent touring historic sites, sitting in restaurants, and discussing surprisingly inevitable romantic matches, is a kind of aesthetic bloodletting, a warding off of inconsequentiality by fully engaging in it. It takes some nerve to engage so faithfully with this kind of beauty, especially when the art world around you is set on dismantling the relevance of a bourgeois sensibility in art.

The middle-class familial routines of Freilicher’s life were at odds with the cold-water flats and daily poverty that characterized the downtown painting world in the thirties and forties, its attendant machismo that Freilicher thought “was not terribly interesting” but which many painters of her own generation were prone to idealize. Critical concern was not so much with Freilicher’s difficulty, but with her appeal; commenting on the New York Times’s decision not to review one of her exhibitions in 1971, Schuyler wrote to Mathews, “Poor Jane . . . I don’t understand it — her work seems to be so filled with appeal; but I guess that’s what Kramer and Canady don’t like in art.”

Yet there is courage in that appeal. Freilicher has presented her desire as purely and as honestly as possible by frankly acknowledging its exact forms. And there is also courage in company. Freilicher described her poet friends’ influence as “a sympathetic vibration, a natural syntax — a lack of pomposity or heavy symbolism.” The pomposity Freilicher refers to here has everything do with the self-conscious iconoclasm of modern art, her response to overly strenuous declarations of life and love. (As Schuyler wrote, her paintings “lacked that authoritarian look, public-spirited and public-addressed, stamped on so much postwar work like a purple ‘ok to Eat’ on a rump of beef.”) In the same letter in which he recommended Proust to Freilicher, Ashbery noted he was reading Pater and his comments on Botticelli’s “peevish-looking Madonnas.” He typed out a section for her he thought particularly fine: “But besides these great men [Michelangelo and Leonardo] there is a certain number of artists who have a distinct faculty of their own by which they convey to us a peculiar quality of pleasure which we cannot get elsewhere; and these, too, have their place in general culture, and must be interpreted to it by those who have felt their charm strongly, and are often the object of a special diligence and a consideration wholly affectionate, just because there is not about them the stress of a great name and authority.” His prescience is clear here, too. Pater’s description fits Freilicher perfectly. There is a photo of her — probably taken during the sixties — standing on the beach in Southampton with Ashbery, smiling, looking directly at the camera. She is quite different from how she appears in Burckhardt’s films: older but happier it seems, freely composed. You can sense the weight of cool mornings and evenings in summer both behind her and before her, the daily routines of middle-aged family and friendship structuring her life, the memorable Labor Day and New Year’s Day parties. A good life. The end of Rivers’s eclogue about Freilicher — her call to friends, announcing coffee — is exactly the kind of response her paintings convey to the world. The beauty of these daily pleasures is more than enough.

This is article is part of a larger portfolio, Jane Freilicher: Painter Among Poets. The first essay in this section is "Leave It to Jane" by John Ashbery.

Acknowledgements

Jane Freilicher: Painter Among Poets will be on display at the Poetry Foundation, 61 West Superior Street, Chicago, Illinois through February. Please visit our gallery page for details.

“Poem (WHE EWHEE)” is from The Collected Poems of Frank O’Hara edited by Donald Allen, published by Alred A. Knopf, Inc., Copyright © 1971 by Maureen Granville-Smith. Reprinted by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

Poetry magazine and the Poetry Foundation would like to thank Tibor de Nagy Gallery for making available their exhibition and catalog, from which this portfolio and our concurrent exhibition are drawn. Special thanks to Eric Brown and Andrea Wells at Tibor de Nagy Gallery for their impeccable organization and correspondence, to Jenni Quilter for her illuminating text, and to John Ashbery and David Kermani for their warmth and generosity. We are also indebted to Karen Koch, Leslie Morris, Ariel O’Hara, John O’Hara, Julie O’Hara, Keith O’Hara, Maureen O’Hara, and Deborah Peasey. We give our greatest thanks and appreciation to Jane Freilicher.

Jenni Quilter teaches writing at New York University. She is the author of Neon in Daylight: New York School Collaborations and Connections (Rizzoli, 2014).

-

Related Collections

-

Related Authors

-

Related Poem

- See All Related Content

Many thanks to The Poetry Foundation for presenting Jenni Quilter's illuminating and knowledgeable essay and for bringing forward to the world this fascinating relationship between visual artists and poets.