James Schuyler in the Spotlight

“That feeling—the story happening as it’s being told—times ten, times a hundred, is what first struck me about James Schuyler’s poems: a specific time, place, room, garden, season, all happening in the present with the kind of balance, detail, and occasion more typical of a painting than a diary. That’s how Schuyler’s poems work for me, what gives them their own charge”—Eric Ziegenhagen reflects on James Schuyler.

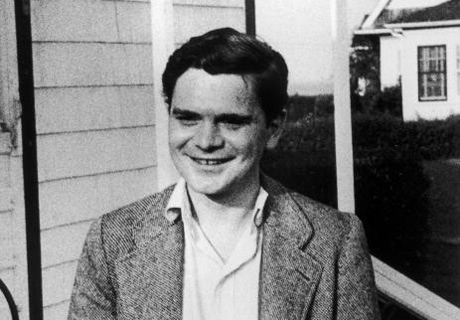

James Schuyler. Image: Getty Images

James Schuyler. Image: Getty ImagesI’m a theater guy. In my field, in my business, when a character addresses the audience, there are two options: he or she is on the stage itself, in front of us, telling a story (see Our Town, Swimming to Cambodia), or the character is speaking to us from a specific place and time other than onstage and right now. The actual actor is always in the present, on the stage, but the character, more often than not, is somewhere else—some other location at some other moment—addressing us from there.

Someone once excitedly told me about seeing a play by Irish playwright Conor McPherson, one in which a guy tells his long, crazy story directly to the audience and then, at the end, puts on a necktie. Suddenly, the audience knows he’s going out, or going to court, or wherever. The reveal is that he is not just talking to us in some nowhere place, or on the stage, but actually speaking to us from somewhere in the world of the story, and that the story is still happening as it is being told.

That feeling—the story happening as it’s being told—times ten, times a hundred, is what first struck me about James Schuyler’s poems: a specific time, place, room, garden, season, all happening in the present with the kind of balance, detail, and occasion more typical of a painting than a diary. That’s how Schuyler’s poems work for me, what gives them their own charge. The poems are grounded in a day, in a place, and sometimes written not for an abstract reader but for a specific person, on a specific occasion. In an essay about naturalism and theater, playwright Steven Dietz once wrote that if people actually talked the way they do in David Mamet’s plays, it would cost $17.50 to get into Chicago. Similarly, if any Joe’s recorded observations read like James Schuyler poems, every grocery list and seed packet would deserve its own chapbook.

Reading Schuyler’s Collected Poems, the theater guy in me thinks of Stanislavski’s method for acting—the speaker of the poem, like a character in a play, has an objective and a motivation, but he also has obstacles that stand in his way (long distance, depression). The act of writing the poem is a solution—but not just because the poet is emoting. He’s specifically, purposefully, creating the poem as a project or a gift, a love letter, a postcard, a birthday present. Often with Schuyler, the postcard poems—like those in the “Loving You” section of The Crystal Lithium (1972)—are more of a wish-I-were-there than a wish-you-were-here. Even more often they are a here-I-am-and-I-will-tell-you-in-every-way-inside-and-outside-me-what-“here”-is-this-morning with some gallows humor and some memory or longing thrown in. It’s landscape with emotional baggage. But in the end, there’s a purpose to recording the “here,” a purpose for getting through the day—an activity or a break. They’re lunch hour poems that take all day.

Schuyler’s poems increase in tension as their specific purpose comes closer to the surface. In Schuyler’s last long poem, the glorious “A Few Days,” there is the sense of the preoccupied host making conversation but conveying anxiety. He’s talking about the weather and mundane plans, but he has a particular, nervous pitch that leaves the companion—the reader, the listener—wondering what’s going on here? What’s going on upstairs? Something shifting, hurried, aiming-to-please, distracted, and also entertaining is happening here—shades of Warhol and Capote, or at least how they have been portrayed on film. And then the picture becomes clearer:

It’s no day for writing poems. Or for writing, period.

So I didn’t.

Write, that is. The bruises of my face have gone, just

a thin scab on

the chin where they put the stitches. I’m back on Antabuse:

what a drag. I

really love drinking, but once I’m sailing I can’t seem

to stop. So, pills

are once again the answer. . . .

There’s a sense all through “A Few Days” of searching for the right chemical, the right transformative experience, and that it is within arm’s reach—or if it is not, there is nothing to do but wait for a new day. The holy is in the mundane, and the holy can be reached from time to time through life’s static—static from the brain, static from the body.

But the static is not the primary focus of Schuyler’s poems. In “A Few Days,” he writes:

Let’s love today, the what we have now, this day, not

today or tomorrow or

yesterday, but this passing moment, that will

not come again.

Now tomorrow is today, the day before Labor Day,

1979. . . .

So many of his poems seek the specifics of the day. “Advent”—along with the long poems, one of my favorites by Schuyler—does this in a haiku-like manner: specific emotion, specific weather, specific season. In “Overcast, Hot,” he memorializes, maybe as a joke, the summer of ‘81:

It’s a hot day:

not so hot

as the days before:

it’s that July,

the one in 1981,

the hot one. . . .

In the end, however, he captures a view from a specific place more than a public history, more a postcard than a public document. The effect is not unlike Richard Avedon’s portrait of W.H. Auden. Or, just to take this a little further: other people’s poems remind me of Avedon’s standard portraits—white background, no context to when and where it was written. Schuyler’s poems remind me of the rare work that Avedon did outside the studio. With Auden, Avedon ground the portrait in a specific day and a specific place instead of suspending a vague, unspecified whiteness. Or, to make another analogy and compare contemporaries, while John Ashbery disorients and constantly surprises the reader like Godard, Schuyler is Eric Rohmer. He sticks to chronology and captures emotional and physical texture. He believes in the ability to capture people and objects in an impressionistic manner, to record actual motion in the world. It’s as simple as (in “A Few Days”): “The phone rings./And is answered.” But then also: “I’ll soon forget it./What have I not forgot?”

The nine poems by James Schuyler in the current issue of Poetry—taken from Other Flowers: Uncollected Poems, to be published in 2010—also chart the evolution of his style, as well as experiments and occasions. “Poem (The day gets slowly started)” captures Schuyler’s mature style, gracefully balancing the observational, the overheard, the textural, the emotional, and the cerebral:

The day gets slowly started.

A rap at the bedroom door,

bitter coffee, hot cereal, juice

the color of sun which

isn’t out this morning. A

cool shower, a shave, soothing

Noxzema for razor burn. A bed

is made. The paper doesn’t come

until twelve or one. A gray shine

out the windows. “No one

leaves the building until

those scissors are returned.”

It’s that kind of a place.

These poems also show Schuyler outside his wish-I-was-there mode, actually being there, out of domesticity, at a concert in “Scarlatti” and in Italy itself in “Foreign Parts.”

If I immersed myself in Schuyler-like immediacy and transparency here, I would write about having one pint of beer, sitting at a counter at Whole Foods, facing Halsted Street in Boystown in Chicago on a Friday night in fall 2009—but it wouldn’t be the same. Or would it be, or who am I to say? And if I rewrite this paragraph a week later in a different place—externally, internally; different part of town, after an argument with my girlfriend—do I include that or stick to the original location, the original feeling, and try to deepen that? Do I keep the illusion of a single draft, or capture the layers of revision?

And now I also fight the haze that I sense Schuyler fought as well: the effort to write the next line, the next thought—although the recent unpublished poems, letters, and journals indicate that maybe it wasn’t a struggle. Maybe the rest of his life was the struggle, and writing, after the struggle of getting up, was an easy reprieve.

Eric Ziegenhagen is a stage director, playwright, and musician based in Chicago.

-

Related Collections

-

Related Authors

- See All Related Content

I haven't read Schuyler's work, but the description of it in this essay reminds me of one of my favorite Beach Boys songs, Busy Doin' Nothin'". There's an entire verse, for instance, where Brian Wilson is simply narrating the directions to his house, a wonderfully quotidian moment that also roots the song in a particular place and time (since it's doubtful he still lives there).