Keats in Space

Creative frenzy is one of those subjects that makes for perennially joyful reading, no matter what field or object it takes as its center. Our idea of the single-minded pursuit—feverish, purposeful, overwhelming—is a distinctly Romantic one, and it springs from the poets of the era: Byron, Wordsworth, Blake, Coleridge, Shelley. —Molly Young discusses The Age of Wonder by Richard Holmes.

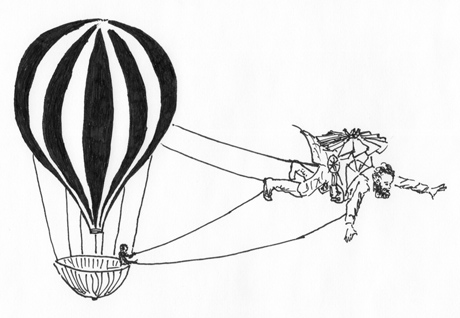

Original illustration by Paul Killebrew

Original illustration by Paul KillebrewCreative frenzy is one of those subjects that makes for perennially joyful reading, no matter what field or object it takes as its center. Our idea of the single-minded pursuit—feverish, purposeful, overwhelming—is a distinctly Romantic one, and it springs from the poets of the era: Byron, Wordsworth, Blake, Coleridge, Shelley. In his new book, The Age of Wonder, Richard Holmes studies the archetype from a different angle or, rather, offers up a new cast of models from whom the Romantic figure might have emerged. These are the scientists of the era, the astronomers, explorers, chemists, and botanists who launched hot air balloons, built 40-foot reflector telescopes, taught themselves Mandingo, and experimented with nitrous oxide. Holmes is less interested in direct lines of influence and affiliation—from, say, Coleridge to Darwin—than he is in redefining the Romantic personality type to include these new explorers, and to explain that it wasn’t necessarily the scientists following the lead of the artists in compiling the Romantic type but something, perhaps, like the opposite.

Romanticism as a cultural force, Holmes points out, is generally regarded as "hostile to science, its ideal of subjectivity eternally opposed to that of scientific objectivity." Yet both pursuits followed the same imaginative principles and notions of wonder that fueled their advancements, and it is Holmes’s contention that a Romantic science exists in the same sense as a Romantic poetry, and both flourished during what he calls the Age of Wonder.

The period begins with Captain Cook’s voyage to Tahiti in 1768 and stretches into the 1830s, during which time science retooled its commitments toward educating the general public—“popular science” was until then unheard of—rather than reserving its practice for the Latin-proficient educated elite. The stars of Homes’s era are Captain Cook, Sir Joseph Banks, Humphry Davy, Mungo Park, and William and Caroline Herschel, and their narratives constitute his evidence for a Romantic science. It’s worth mentioning that Holmes’s working conception of Romanticism is vaporous and broad, and his use of the term less taxonomic than it is evocative. This, however, is not a bad thing. If not quite crystal-cut, his definition makes more intuitive sense than a strict delineation might.

Poems from the Age of Wonder

John Keats:On First Looking into Chapman's Homer

Percy Bysshe Shelley:

from Epipsychidion

Percy Bysshe Shelley:

Alastor; or, The Spirit of Solitude

Percy Bysshe Shelley:

Mont Blanc: Lines Written in the Vale of Chamouni

Samuel Taylor Coleridge:

Fragment 6: The Moon, how definite its orb!

Lord Byron:

Darkness

William Wordsworth:

The Tables Turned

Erasmus Darwin:

Economy of Vegetation: Canto I

Sir Joseph Banks provides the founding myth of the Romantic explorer, and he proves as engaging a character as Byron or Trelawny. A botanist and diplomat by trade, Banks sailed to Tahiti in 1768 with Cook and kept careful logs of his trip. The diaries include lists of vocabulary, recipes for roasted dog, and an account of a young Tahitian woman having her buttocks tattooed. Most striking in Banks’s journals is the intensity of his curiosity and its mingling with affection and concern for the objects of study. The tenor of the young botanist’s study is not disinterested; it is yearning, and he cuts an appealing figure. It is no surprise that William Cowper cast Banks as an intrepid bee in his poem The Task.

William Herschel was the second figure to fit the new mold. An astronomer of “acute unconventional intelligence” with a “quick, boyish enthusiasm, that betrayed intense and almost unnerving passion,” Herschel was an accomplished professional musician (in his spare time composed an oratorio based on Paradise Lost). He was once thrown from his horse only to somersault and land upright still holding a book in his hand. He considered the episode a perfect demonstration of Newton’s law of circular motion. The age of Romantic science was full of such endearing figures: men and women who devised spectacular plans, ignored common sense, nursed frivolous whims, and devoted themselves with unhealthy enthusiasm to their work.

If the scientists of the era seem so far to bear none but a temperamental relation to the poets, consider a few facts. For one thing, the arts and sciences were more closely intermingled in the 18th century than they are today. A popular astronomy book contained illustrative poetry from Milton and Dryden; Erasmus Darwin (grandfather of Charles) recorded one of Herschel’s discoveries in his 1791 poem The Botanic Garden and produced the best-selling long English poem of the decade. Herschel himself acknowledged that “Seeing is in some respects an art, which must be learnt.” A young Samuel Coleridge was taken out into the fields nightly by his father to be shown the sky, and cosmological imagery figures richly in his early poetry.

If this seems a far cry from our contemporary era of antiseptic specialization, well, it is.

Providing a material link between poetry and science in the Age of Wonder is the chemist Humphry Davy. A “small, volatile, bright-eyed” man “bursting with energy and talk,” Davy wrote verse when he wasn’t measuring the cubic capacity of his own lungs or investigating the strange pleasures of nitrous oxide, to which he introduced both Robert Southey and Coleridge. Davy likened scientific lecturing to poetry in his own mind; both were opportunities to devise narratives with potential to hold an audience captive. Coleridge became a great admirer of Davy and a subsequent defender of science, noting that “being necessarily performed with the passion of Hope, [science] was poetical.” Davy usually conducted his experiments independently, outside of institutions that might question his peculiar methods. Throughout his career he continued to produce verse—some published and some private—including one sketch that described the dead Lord Byron riding a comet around the universe.

The literary current ran both ways: Byron wrote Davy into the first canto of “Don Juan”; Shelley planted Davy’s ideas in 1812’s “Queen Mab” and, eight years later, in “Prometheus Unbound”; Keats’s “Lamia” is full of chemical imagery, and Coleridge’s “Kubla Khan” echoes Banks’s voyage to Tahiti in its depiction of an irrecoverable and hallowed distant place. Keats’s sonnet “On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer” (1816), written after a night poring over translations by the scholar George Chapman, is a particularly keen example of entangled scientific and poetic sensibilities. Although the poem does not name William Herschel, it heralds the astronomer’s discovery of Uranus as the embodiment of wonder, exploration, and epiphany (“Then felt I like some watcher of the skies / When a new planet swims into his ken”). The sonnet compares a reader’s moment of transcendence with that of a scientist; both are “watchers” whose metaphysical transformation hinges on a visual experience.

The consensus on either side was that both science and poetry had not only an intellectual magnificence but a spiritual, emotional, and philosophical magnificence as well. It was the shared habit of Romantic scientists and poets both to put as much stock in the process of discovery as in discovery itself, and it is this particular fever that is Holmes’s fascination.

The fever itself was short-lived. Davy, Banks, and Herschel were all dead by 1830, and their passing clearly signaled the end of an era. Thomas Carlyle announced the end of Romanticism in his 1829 tract Signs of the Times, and Charles Babbage nailed the coffin shut with 1830’s Reflections on the Decline of Science in England. Thus began the era of Victorian Science, with its increased specialization and institutionalizing of what had once been a messy and boundless study. The mood of the field was no longer one of rapidity and ambition; intellectual pursuits were permanently fractured. There was no one left to define brilliance, as Coleridge did, as a form of cultivated wonder.

In this respect, Holmes’s book is an odd thing to behold. It is equal parts passionate history and head-shaking elegy—a recovery of a golden era and a subsequent burial of it. Gaining access to a bygone world of cosmic thinkers is startling and revelatory for the average reader; necessarily, then, the account of their decline feels like an unbearable loss.

If the book closes with an elegy, it contains, at least, the promise of regeneration. What Holmes has given us with this account of the Romantic scientists is, curiously enough, a thrilling new way to interpret the poets of the era. To bring new light to such a widely read group—and from the angle least expected, that of rigorous scientific study—is Holmes’s considerable gift.

Molly Young's writing has appeared in n+1 and the New York Observer.

-

Related Collections

-

Related Podcasts

- See All Related Content

Science poem from Emily Dickinson

http://www.poetryfoundation.or...