The Convert

I think about Margaret Danner often when I enter the Newberry Library, where I work. Here, Danner would have stepped through the arched entrance on Walton Street, a Romanesque exterior of pink granite designed by Chicago architect Henry Ives Cobb. She would have walked through a lobby tiled with stone mosaic. On days when she did not want to climb five flights of stairs to the offices of Poetry magazine, which then operated out of the library—and where she was an assistant editor—Danner would have taken the elevator.

Danner’s metafictional poem “The Elevator Man Adheres to Form” first appeared with this epigraph: Not really the elevator man at Newberry Library. Perhaps the figure in the poem embodies many kinds of men: he is a “tan man who wings the elevator,” a Black man who is light-skinned, who displays his comportment and “Ph D aplomb” as a means of upward mobility. Yet despite his education, he is still consigned to employment as an elevator man, in acquiescent service to library patrons. He almost certainly would have been the only other Black person at the Newberry when Danner worked at Poetry.

If the speaker of this poem bears any resemblance to Danner herself—a Black woman in a circle of mildly condescending poetry editors at a research library where everyone was white—then her ride to the fifth floor was a moment of preparation and passage, a lift through a shaft, the final daily ascent from the South Side of Chicago where she lived to the editorial tables of Poetry. The poem wonders how the elevator man’s Blackness squares with the lives of “other tan and deeper much than tan” men who are not lifted up, but rather cast down into “subterranean grottoes of injustice.” What responsibility does the elevator man have to these underground, working-class Black people? Or to her, the Black poet whom he “gallantly” escorts to the top floor?

In her poem and in his “polished pleasantries,” both Danner and the elevator man seek a language of Black unity in the face of social difference. Before she became a member of the Baha’i faith in the early sixties, and before the emergence of the Black Arts Movement that celebrated Black pride, resistance, and solidarity, Danner sought to express a connectedness among people, writing poems that wove her experiences into the dream of a universal human pattern. Lace is a frequent motif in Danner’s work: from the lace of a christening dress to the interlacing architectural motifs in the massive, white-domed Baha’i temple in the Chicago suburb of Wilmette to the lace-like filigree of iron in the fences of New Orleans, built by enslaved artisans such as Samuel Rouse in Danner’s poem “The Slave and the Iron Lace.” Her poetry itself is a lacework of rhyme, prosody, and syntax that seeks to integrate otherwise irreconcilable social and personal elements into an art of formal complexity.

Throughout her life, Danner laced herself into multiple realms, not always sure how her own aspiration connected to others who shared her commitment to poetry. In 1941, she joined what would become a legendary Wednesday evening poetry workshop at the South Side Community Art Center (SSCAC), taught by a white woman, Inez Cunningham Stark. The workshop was composed of artists and writers of extraordinary talent and ambition, including Gwendolyn Brooks, who was then working on the poems that would become A Street in Bronzeville. Others included Edward Bland, a promising poet who would die tragically in WWII; John Carlis, who would become a well-known artist; William Couch, a charismatic writer who attracted Brooks’s attention (and made his way into at least two of her poems, as well as her only novel, Maud Martha); Margaret Burroughs, an artist, activist, and writer who would go on to found the DuSable Museum of African American History; and Fern Gayden, who coedited Negro Story from 1944–1946. This was Danner’s early Chicago cohort, a circle of writers and artists with whom she learned, swapped books, and often disagreed.

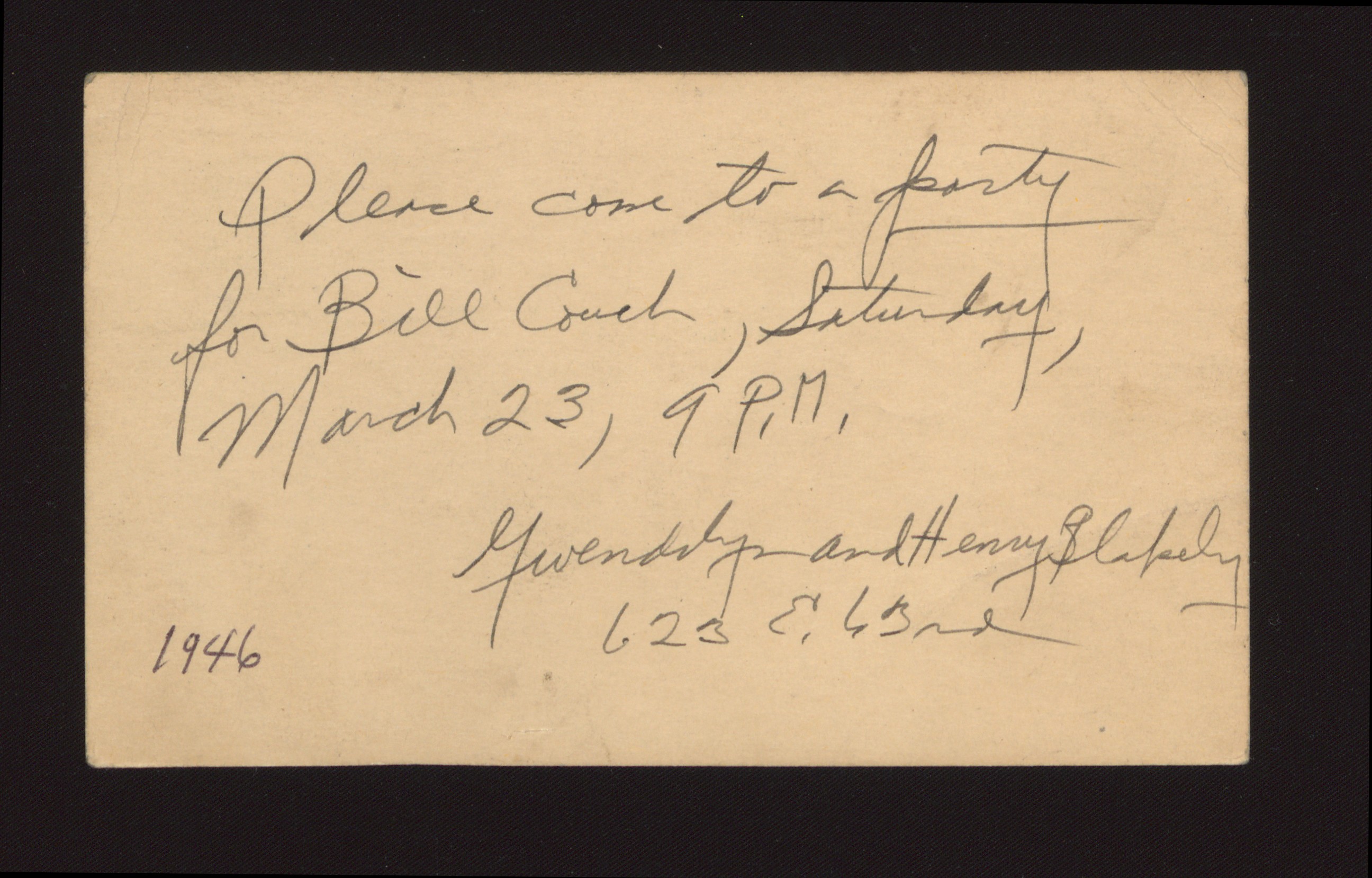

Danner’s papers at the University of Chicago are not extensive—two boxes—but her letters suggest that she could be competitive with others, distrustful of certain people’s intentions, and uneasy with those she perceived as threatening. After a party for William Couch in 1946 at the home of Gwendolyn Brooks, for instance, Danner wrote a tortured letter to Brooks, expressing surprise that she was invited, and apologizing for her behavior. “I am not really like the moods that possess me at times,” Danner tells Brooks. This self-difference, or the disconnect between identity and affect, may furnish one of the most universal elements in Danner’s work.

Like her SSCAC poetry teacher Inez Stark, Danner was a boundary-crosser, riding up to “5” on the elevator to the offices of Poetry magazine. Years before the founding of OBAC (the Organization of Black American Culture) and AfriCOBRA (the African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists), she fashioned her own cultural politics from a home-grown Pan-Africanism. Poetry editor Henry Rago published the poems that would become Danner’s most anthologized, including “The Painted Lady,” a nine-line poem that describes a “small African/Butterfly gayly toned deep tan and peach.” The color “tan,” which also describes the elevator man, is a motif as frequent in Danner’s work as lace. (This affinity for “tan” may indicate Danner’s ambivalence about the binary of Blackness versus whiteness.) The “tan and peach” butterfly is both delicate and tough, migrating long distances from the deserts of Africa to the gardens of Europe. “This cosmopolitan/Can cross the sea at the icy time of year/In the trail of the big boats, to France.” The final triplet of the poem wonders about the “strength” of the poet’s own colors and art:

Mischance is as wide and grey as the lake here

In Chicago. Is there strength enough in my

Peach paper rose or lavender sea-laced fan?

What connection does Chicago have to Africa, or the female poet to feminist politics? Will writing on “peach paper”—the making of her art—be enough to find connection and meaning across seas and continents? Perhaps. And yet Danner fears “mischance,” stray winds over a big grey lake.

Danner’s sense of her own precarity—blown about by winds, delicately poised between realms—reappears in the collaborative chapbook Poem Counterpoem (1966), coauthored by Danner and Dudley Randall. Bright yellow with bold red lettering, Poem Counterpoem was published by Randall’s Broadside Press, a groundbreaking vehicle of the Black Arts Movement. The back cover announces that the chapbook is “unique in all literature” for its collocation of “poems arranged in pairs,” in which “the authors treat the same or similar subjects.” Indeed, the call-and-response structure of the book is like conversation, or musical form, a positioning of one voice in distinction from the other. Danner’s precarity in this collaborative performance is most apparent in her poem “I’ll Walk the Tightrope” where the poet imagines a high path that she must traverse alone:

I’ll walk the tightrope that’s been stretched for me,

And though a wrinkled forehead, perplexed why,

will accompany me, I’ll delicately

step along. For if I stop to sigh

at the earth-propped stride

of others, I will fall. I must balance high

without a parasol to tide

a faltering step, without a net below,

without a balance stick to guide.

Other people “stride” the solid earth but Danner must “step above” them. The speaker of the poem is without support, no “parasol” or “net” or “balance stick.” Uncertain of her aim, but too scared to stop, her prosodic feet must walk a poetic line “that’s been stretched for me.” Or perhaps she has chosen her own virtuosic elevation. It’s a remarkable description of solitude in a volume of poetry structured by collaboration and counterpoint.

Dudley Randall’s poem in response to Danner’s solitary tightrope performance, simply titled “For Margaret Danner,” features the epigraph “In establishing Boone House”—a sly reminder that Danner did not walk alone. A cultural center that Danner founded in Detroit for Black artists, musicians, and poets, Boone House took its name from the pastor of King Solomon Church, Dr. Theodore S. Boone, who had allowed Danner to take over its empty parish house from 1962–1964. Under her direction, Boone House served as the literary headquarters for what would become known as the “Detroit Group”—including Randall, Naomi Long Madgett, Woodie King Jr., and Oliver LaGrone—hosting visits from distinguished literary figures such as Robert Hayden, Hoyt Fuller, and Langston Hughes. Danner may have expressed in her poetry a profound sense of isolation, but she worked quite visibly through Boone House—and during her extended residencies at Wayne State University, Virginia Union University, and LeMoyne-Owen College—to build a literary community of her own.

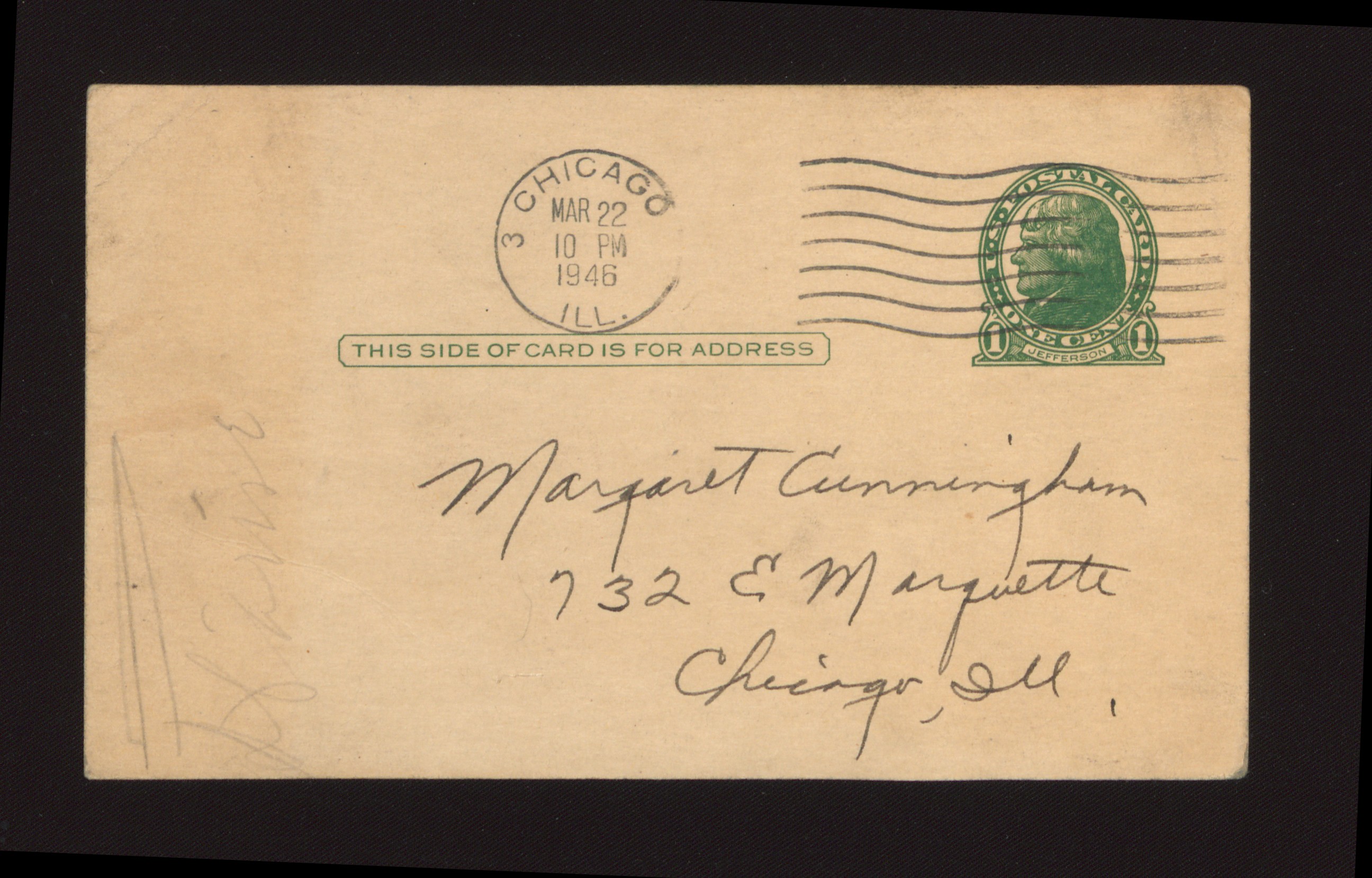

Postcard (front) from Gwendolyn (Brooks) and her husband Henry Blakely to Margaret Danner inviting her to a party at their home in honor of writer William Couch, March 22, 1946. Danner used the last name Cunningham after she married Otto Cunningham. From the Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library.

Postcard (back) from Gwendolyn (Brooks) and her husband Henry Blakely to Margaret Danner inviting her to a party at their home in honor of writer William Couch, March 22, 1946. From the Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library.

In the early sixties, during Danner’s time in Detroit, she converted to Baha’i, an Eastern faith founded by a nineteenth-century Persian leader who believed in the universality of all religions. Danner shared her faith with Robert Hayden, who taught for many years at Fisk University, and whom Danner deeply admired. Being Baha’i nurtured a spirit of generosity in Danner and may have been the “tightrope” that lifted her above a younger set of poets with whom she did not always agree. Her Baha’i faith also furnished a universalizing alternative to the separatist and segregationist black-and-white religious factions of her time.

Even as she participated in her own quiet versions of literary activism at Boone House, Poetry magazine, and beyond, Danner’s universalizing views of art and society suggest her ambivalence toward certain forms of political activism. In a May 8, 1967, letter to Hayden, on returning from a poetry reading at Fisk, Danner expresses her bewilderment at the radical spirit of LeRoi Jones, also known as Amiri Baraka.

Fisk was really jumping and I needed you, although I did get a long standing ovation. And much praise. I told it as it was and took Le Roi Jones into my bedroom and tried to reason with him. He had those kids walking the walls with incredible four letter words under the name of poetry.

She describes her intervention with Baraka as if she were a mother reprimanding an unruly child. Danner remained aloof from—or rather, she might say, above—the revolutionary aims of the Black Arts Movement. It is unclear how she imagined racial and political progress, but she emphasized to Hayden that her ideas about poetry did not square with the radicalism of a younger generation of Black poets. “There is so much that we should talk about both being Baha’is and both being non-political,” she wrote to Hayden in March 1968. Nine months later, when she was poet-in-residence at Virginia Union, she wrote to Hayden: “I do not know what is happening to any other writers since Negro Digest seems to have gone completely political. Please write and tell me if you would think of coming down, not to the militant group but to one of the other higher level poetry appreciation groups.” Danner’s reference to “higher level” poetry communities suggests that the author of “The Elevator Man Adheres to Form” has yet to fully free herself from the hierarchical literary cultures of her time.

But Danner’s commitment to the cultures of Africa, even before she first traveled there in 1966, informs a cultural radicalism that animates her Pan-Africanist politics, of which she was deeply aware. Her wonderful poem “The Convert” describes a formative exposure to African art, in 1937, through the collection of Etta Moten Barnett, the famous singer, philanthropist, and doyenne of Black Chicago. When Barnett, “sweetheart/of our Art Study group” presents a “hideous African nude” as a figure for their study, the speaker of the poem is repulsed by the statuette’s “huge bulging blots/of its lips and nose.” The nude’s “navel, without a thread of covering,” makes Danner dread looking at it. But over time, with “the turn of calendar pages,” the speaker begins to see the figure’s beauty:

The same symmetrical form was dispersed again

and again through all the bulges, the thighs

and the hands and the lips, in reverse, even the toes

of this fast turning beautiful form were a selfsame chain,

matching the navel. This little figure stretched high

in grace, in its with-the-grain form and from-within-glow,

in its curves in concord. I became a hurricane

of elation, a convert undaunted, who wanted to flaunt

her discovery, parade her fair-contoured find.

The poem bears comparison to Rainer Maria Rilke’s “Archaic Torso of Apollo,” a poem about an encounter with a statue “suffused with brilliance from inside,/like a lamp, in which his gaze, now turned to low,//gleams in all its power.” The sexual power of Apollo’s form, like Danner’s African figure, spurs a spiritual revelation in Rilke’s poem, which ends with the famous lines, here in Stephen Mitchell’s English translation: “for here there is no place/that does not see you. You must change your life.”

Danner did change her life, again and again. She was a perpetual “convert,” reviving and celebrating African culture, pursuing her literary evangelism at Boone House, and attesting to the Baha’i faith. Amid the “hurricane of gargoyles” blasting out social unrest in the period, this writer’s inward “hurricane/of elation” became a sustained language of poetic praise. It spilled over into letters of gratitude. “i love everybody. all of my enemies and everyone, just anyone at all,” she typed in all-capital letters to thank Etta Moten and Kathryn Dickerson, another prominent Black Chicagoan and arts patron, for coming to her poetry reading in Detroit. Danner could feel nurtured and supported by her community—here, two Black women—and she channeled that feeling into poetry’s earliest form, a ritual form of prayer.

Poems for Danner became a raising up of oneself to a higher power, an elevation of the soul. Her poem “Through the Varied Patterned Lace” includes the performative epigraph: “Greeting from a Baha’i/“I salute The Divinity/in you.” The poem expresses the poet’s unity with “each different face,” rhymed artfully with “race,” through which she recognizes “His Grace.” In the violent year of 1968, to publish these lines of praise must have been an effort, a willed conviction:

Divinity must win the race. It will not be halted.

We are all small sons of one clan.

I am exalted.

Exalted is to be elevated, lifted up. But there is no elevator operator facilitating the exaltation in this poem. Exaltation is a language that belongs to Danner herself, who appeals to a spiritual realm above the politics of division and unity alike, the residence and dwelling of “one clan” far beyond a library’s fifth floor. It was no doubt a difficult elevation at which to live.

Liesl Olson is the author of Modernism and the Ordinary (Oxford University Press, 2009) and the literary history of Chicago, Chicago Renaissance: Literature and Art in the Midwest Metropolis (Yale University Press, 2017), winner of the Poetry Foundation's 2018 Pegasus Award in Poetry Criticism. She has been the recipient of fellowships from the National...

-

Related Collections

-

Related Authors

- See All Related Content